Health Coverage for the High-Risk Uninsured:Policy Options for Design of the Temporary High-Risk Pool

By Mark Merlis

Among the first tasks required by the recently enacted health reform law is creation of a temporary national high-risk pool program to provide subsidized health coverage to people who are uninsured because of pre-existing medical conditions. While as many as 5.6-million to 7-million Americans may qualify for the program, the $5 billion allocated over four years will allow coverage of only a small fraction of those in need, potentially as few as 200,000 people a year. Policy makers will need to tailor eligibility rules, benefits and premiums to stretch the dollars as far as possible. Another consideration is how the new pool will fit with existing state high-risk pools or other state interventions in the private nongroup, or individual, health insurance market. Policy makers also will need to consider how to manage the transition of enrollees from high-risk pools to the new health insurance exchanges scheduled to be operational in 2014 to prevent adverse selection and encourage insurer participation.

- Bridging the Coverage Gap for the High-RiskUninsured

- Temporary Pool Provisions

- Estimating the Target Population

- Policy Options

- Eligibility

- Other Eligibility Rules

- Benefits

- Premiums

- Treatment of Existing State Programs

- Looking Ahead

- Notes

- Data Source

Bridging the Coverage Gap for the High-Risk Uninsured

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) of 2010 includes insurance market reforms and income-based subsidies designed to make health coverage more accessible and affordable. Most of these measures do not take effect until January 2014. Until then, people with pre-existing medical conditions who lack access to employer-sponsored or public coverage may continue to have trouble finding affordable coverage in the private nongroup, or individual, market (see box below for more about underwriting practices in the nongroup market and state regulatory responses). To bridge the gap, the new law provides for an interim national high-risk pool, modeled on those already operating in 35 states (see box below for more about state high-risk pools). Possibly starting in some states as early as July 1, 2010, the program will provide subsidized coverage to uninsured people with pre-existing medical conditions. This analysis summarizes provisions of the new temporary high-risk pool program, estimates the population that might be eligible and reviews some of the key policy issues that must be resolved as the program is implemented.

Underwriting and Regulation in the Nongroup Market

Nongroup health insurers commonly obtain information on an applicant’s current health status, medical history and other indicators of future medical costs. If an applicant is determined to be high risk, an insurer may:

- refuse to issue a policy;

- issue a policy with an exclusion or elimination rider, under which services for a specific condition are temporarily or permanently excluded; or

- Charge higher—substandard—premium rates than would be offered to comparable individuals who are not classified as high risk.

Insurers also commonly impose pre-existing condition exclusions on all new policyholders, regardless of their perceived risk level. For a fixed period, such as six or 12 months, no coverage is provided for any medical condition the purchaser has at the time coverage takes effect or during a look-back period, typically 12 to 24 months before the application. (Many people misunderstand the phrase, ’pre-existing condition exclusion,’ to mean refusal to issue a policy. The phrase properly refers to a temporary restriction on coverage in a policy that has been issued.)

Most states regulate at least some practices of nongroup insurers, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation’s statehealthfacts.org Web site. In 16 states there is some guarantee of access to nongroup coverage, whether from multiple insurers or from a single so-called carrier of last resort, such as a Blue Cross plan. The ability of nongroup insurers to vary premiums by medical condition or health status is restricted in 18 states. Just one, New York, requires community rating—a single rate for all applicants—while six others allow adjusted community rating, with rates varying by age or other non-health factors.

The other 11 allow rate bands, meaning rates may vary by health risk but only within fixed upper and lower limits. Overall, 24 states and the District of Columbia have either issue or rating rules; only nine have both types of rules. Most states also have some restrictions on the use of pre-existing condition exclusions, although none prohibit them entirely.

State High-Risk Pools

High-risk pools are state-operated or state-chartered programs that offer subsidized coverage to people with health conditions that prevent them from obtaining affordable coverage in the nongroup market. In many states, the high-risk pool also serves as the mechanism for providing insurance to people eligible for coverage without any pre-existing condition exclusions under the 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) because they have recently lost employer coverage. Likewise, many state pools provide coverage for people eligible for the Health Care Tax Credit (HCTC) Program established as part of the Trade Act of 2002. The HCTC program pays part of the health insurance premiums for workers displaced by trade and early retirees receiving benefits from the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation.

Currently 35 states operate high-risk pools, with total enrollment estimated at 199,418 in 2008, and 72 percent were eligible because they were ’medically uninsurable,’ according to a 2009 U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) analysis. An insurer may refer people to a state-operated pool, or individuals may apply to the pool on their own. Applicants must demonstrate that they have been denied coverage for health-related reasons by one or more insurers or—in some states—that they have a condition that would lead to denial of coverage. States also allow enrollment by people who have been offered coverage only at very high rates. Premiums paid by risk-pool enrollees are typically capped at between 125 percent and 200 percent of the standard premium’that is, the premium that nongroup insurers might charge an applicant of the same age and sex, in the same geographic area, without known medical problems.

Because the pools are designed to attract the highest-risk applicants, even these higher premiums are insufficient to meet claims costs. In 2008, premiums covered 54 percent of costs in an average pool, according to the GAO. Every pool relies on some form of additional funding to subsidize pool losses. In 29 states, health insurers pay an assessment based on their share of total health insurance premiums earned in the state. These assessments are imposed both on nongroup and group premiums but not on self-insured employer plans, although some states do assess stop-loss carriers used by self-insured plans, according to the National Association of State Comprehensive Health Insurance Plans. Some states also use general revenues, tobacco settlement money or other special funds. Since 2002, there has been a federal grant program for state high-risk pools, with $75 million allocated for 2010.

Even after subsidies, risk-pool premiums can be quite high. The median state pool rate for a 50-year-old male nonsmoker in 2008 was $6,288 a year, according to GAO. Rates ranged from a low of $3,300 in Idaho to a high of $10,176 in Oklahoma for the most popular plan in each state’s pool. Twelve states offered some form of subsidy to low-income participants in 2008, with an average upper-income limit of 285 percent of the federal poverty level’$29,640 for an individual in 2008’and an average maximum discount of 66 percent of the premium. Because subsidy funds are limited, a few states have resorted to waiting lists for pool applicants; one pool, Florida’s, has not been open to new enrollees since 1991. In addition, all but two imposed pre-existing condition exclusions in 2009—meaning that people admitted to the pool because of a medical problem often have to wait six or 12 months before treatment of that problem is covered, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation’s statehealthfacts.org Web site.

Source: U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), Health Insurance: Enrollment, Benefits, Funding, and Other Characteristics of State High-Risk Health Insurance Pools, letter to congressional requesters, Washington, D.C. (July 2009)(GAO-09-730-R)

Temporary Pool Provisions

Under section 1101 of the PPACA, the secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is charged with establishing the temporary high-risk pool program within 90 days after the law’s enactment. The program is to continue operations until Jan. 1, 2014, when the new health insurance exchanges are available. The law allows an extension of pool coverage beyond that date if necessary to assure a smooth transition of enrollees into the exchanges. The HHS secretary can either operate the high-risk pool program directly or through contracts with states or nonprofit private entities.

HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius wrote an April 2, 2010, letter to governors and state insurance commissioners, asking for expressions of interest in participating in the program. Further policy guidance was provided in a solicitation of state proposals to operate pools issued by HHS on May 10, 2010.1

Program structure. HHS has indicated that states may operate a new high-risk pool’either alone or alongside an existing pool—build upon other existing coverage programs for high-risk individuals or contract with a current carrier of last resort or other carrier to provide subsidized coverage. If a state does nothing, HHS will administer the coverage program in that state. As of May 21, 2010, 29 states and the District of Columbia had signaled an interest in operating their own programs, while 19 states declined to participate. Rhode Island and Utah were still deciding (see Supplementary Table 1 for a list of state decisions).

Eligibility. The program is open to citizens and legal residents who have a pre-existing condition, as determined in a manner consistent with guidance issued by the secretary. Applicants also must have been without creditable coverage for at least six months—creditable coverage includes most group and nongroup private health insurance, Medicare, Medicaid and some other public programs. HHS has indicated that it will allow states with existing pools to follow their own criteria for defining pre-existing conditions, subject to HHS approval.

Benefits. Benefits to be provided by the pools are not specified, but the pools must cover at least 65 percent of the cost of whatever services are covered. The coverage also must have an out-of-pocket limit—the sum of deductibles, coinsurance or copayments—no greater than the limits established for high-deductible health plans linked to health savings accounts: $5,950 for an individual and $11,900 for a family in 2010. HHS is considering establishing a ’floor set’ of benefits, taking into account benefits already offered by state pools. The new temporary pools are prohibited from imposing pre-existing condition exclusions.

Premiums. Premium rates may vary only by age, family type (individual vs. family), geographic area and tobacco use. The highest age rate may be no more than four times the lowest. (The age rating rules for regular nongroup and small group coverage to take effect in 2014 specify a 3:1 ratio.) According to the law, rates must ’be established at a standard rate for a standard population.’ That is, they must be equal to 100 percent of the rate that nongroup insurers in the same area would offer for comparable benefits for a population that did not present high medical risk.

Funding. Congress appropriated $5 billion to pay for the pools’ claim and administrative costs in excess of premium revenues during the period July 2010 through December 2013. This comes to about $1.4 billion per year, or about twice the $800 million states spent subsidizing high-risk pools in 2008. HHS has indicated that it will allocate funds across states using a formula comparable to that previously used for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Each state’s share will be based on its total nonelderly population and its uninsured nonelderly population, with an adjustment for state differences in average health sector wage levels (see Supplementary Table 1).

Adjustments. Under the law, the HHS secretary has two ways of keeping spending within the $5-billion limit. The first is a general authority ’to make such adjustments as are necessary to eliminate’ any projected deficit for a fiscal year. The second is an authorization to ’stop taking applications for participation in the program.’

Maintenance of effort. If a state that already operates one or more risk pools enters into a contract to operate a pool under the new program, it must agree to continue to spend each year what it spent in the year before entering the contract on the existing state pool. Interestingly, if a state decides not to contract, and HHS instead provides coverage in that state directly, the state has no maintenance-of-effort requirement.

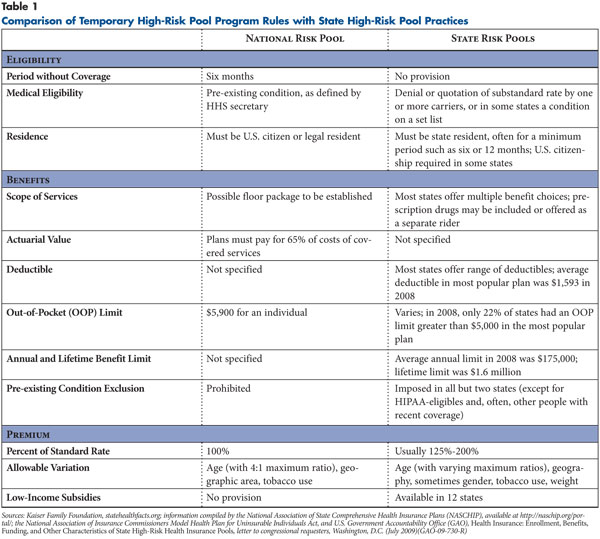

Anti-dumping rules. The law has provisions meant to assure that insurers and employers do not attempt to shift high-risk enrollees from their coverage to the pools. Under these provisions, the HHS secretary must develop criteria to determine whether insurers or employers have discouraged an individual from keeping existing health coverage based on the individual’s health status. Some of the rules governing the temporary national high-risk pool program are quite different from those commonly applied in existing state pools (see Table 1).

Estimating the Target Population

In considering policy options for implementation of the temporary national high-risk pool program, it is useful to understand the size and characteristics of the uninsured population potentially eligible to participate. The 2007 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) allows estimates of the uninsured population at a point in time as well as changes in the population over time.

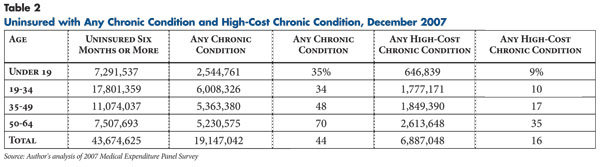

About 51.6 million nonelderly people were uninsured in December 2007—the most recent full year of available MEPS data. Of these, 43.7 million—85 percent of the total—had been without insurance for six months or more, as required by PPACA.2 Children were slightly less likely to have long periods without coverage; 74 percent of uninsured children in December 2007 had been uninsured for six months or more.

Of the people uninsured for six months or more, 44 percent reported at least one chronic condition as defined by AHRQ’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) As expected, the prevalence of chronic problems rises sharply with age (see Table 2). Not all chronic conditions as defined by HCUP result in high medical spending or would be likely to lead to rejection or a substandard rate. For this analysis, a chronic condition is a high-cost condition if people in a given age group with that condition would be expected to have claim costs at least 50 percent higher than average claim costs for the age group (see the Data Source for a description of how these conditions were identified). That is, people with the condition could be expected to receive a rate quotation of at least 150 percent of a standard rate—if they were offered coverage at all. High-cost conditions are even more heavily concentrated among people aged 50-64 than chronic conditions in general.

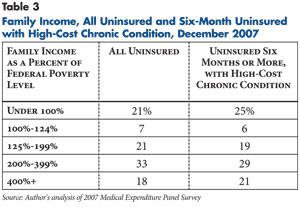

Income distribution is similar for all nonelderly uninsured people and for those who may be thought of as the target group for the temporary high-risk pool program—those uninsured for six months with a high-cost condition (see Table 3). Half of the target group has income above 200 percent of poverty, and one in five is at 400 percent of poverty or higher. While these people may face underwriting barriers, they might be able to afford even a substandard premium (within limits) or pay higher cost sharing than other members of the target population. This is worth considering when thinking about how best to focus limited funding for the temporary pool program.

Finally, many people potentially eligible for the program have access to alternative sources of coverage. Of the nearly 7 million people with high-cost conditions who had been uninsured for six months or more in December 2007, 14 percent were offered coverage through their current employment, similar to the uninsured in general. Many more might be able to obtain coverage as dependents through a family member’s employment; access to dependent coverage was not modeled for these estimates.

Possibly some others of the target population could qualify for Medicaid, although many adults would be excluded by the categorical restrictions that will continue to apply in most states until 2014. Low-income children might qualify for CHIP. Of 646,839 children in the target population, 369,488—or 43 percent—had incomes below 200 percent of poverty. They would have been eligible for Medicaid or CHIP in 44 states as of 2009.4

Policy Options

In implementing the temporary high-risk pool program, the HHS secretary will need to make many decisions about eligibility, benefits, the method for setting premiums and other issues. These decisions will directly govern the design of the national program for non-contracting states and will also set the parameters for federally funded state-operated pools. This analysis focuses chiefly on the choices that must be made at the federal level and not on the additional decision making that will occur in individual states.

The major constraint on policy makers at all levels is the very limited funding for the program relative to the population in need. Until enrollment criteria are established, it is impossible to project just how many people might qualify for the temporary pool program. As noted earlier, using one plausible definition of the eligible population, almost 7 million people are potential participants, or about 5.6 million if those with access to other coverage were excluded. The $5 billion in federal funding is sufficient to provide subsidized coverage to only a fraction of potentially eligible people.

The Office of the Actuary, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), projected that 375,000 people would be enrolled in the temporary pool program in 2010 but concluded that federal funds would be exhausted ’[b]y 2011 or 2012.’5 The number of people who could be covered for the full term of the program might be considerably smaller, particularly because the law precludes some cost-saving measures adopted by state pools and requires that premiums be no more than 100 percent of a standard rate. In 2008, state high-risk pools’ costs per participant exceeded premiums by $4,200. If a $4,200 subsidy was needed to bring premiums down to the typical 125 percent-150 percent of standard rates, the subsidy needed to bring premiums to 100 percent of standard rates would have been in the range of $6,000 to $7,000. If federal subsidies of this size were provided for the three-and-one-half-year life of the program, the annual number of people who could be covered would be around 200,000.

Of course, not everyone in need is likely to apply, particularly if the pools require payment of full standard premium rates without low-income subsidies. Still, the available funding is sufficient to help only a very small share of the population in need.

It is likely that policy makers at both the federal and state level will have to choose between two basic courses. They can simply open the doors to programs that are more generous than most current state pools and allow the programs to reach capacity. There might then be pressure for supplemental funding—although current rules would require that any additional spending be offset by new revenues or offsetting spending cuts. Or they can look for ways to limit entry to the program to those most in need and/or to stretch the dollars to serve more people. How much leeway they have to modify the outlines of the program is uncertain.

As noted earlier, the HHS secretary has the authority to make ’adjustments’ in the program to keep it within budget. It is not clear whether this authority is meant to allow only minor tinkering with program provisions (such as the rule that the pool cover 65% of benefit costs) or would allow more substantial changes in program design, such as charging more than 100 percent of a standard rate or imposing pre-existing condition exclusions. The statutory language does not appear to leave some provisions adjustable and others inviolable, so the discussion here will consider some options that override explicit PPACA provisions. It will also assume that the secretary can proactively make adjustments at the very outset of the program, on the basis of projected funding shortfalls, without waiting for deficits actually to appear.

Eligibility

There are two key issues in determining the eligible population. The first is how to define a pre-existing condition. The second is whether the secretary can establish additional eligibility requirements and, if so, what these should be.

Defining a pre-existing condition. The National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) Model Health Plan for Uninsurable Individuals Act, the prototype used by many states in developing their risk pool authorization laws, outlines two different ways of defining people medically eligible for the pool. First, a person may have been refused ’substantially similar’ coverage by at least one insurer or offered coverage only at a rate higher than that offered by the pool. (Note that this is, by definition, a substandard rate, because no state pool offers a standard rate.) Second, a person can have a condition on a list of ’presumptive conditions’ established by the pool; these are conditions that would usually lead to a coverage denial. State lists have as few as 16 or as many as 80 presumptive conditions.

As some analysts have noted, requiring applicants to first seek coverage in the nongroup market is time-consuming and burdensome, as nongroup applicants must typically make a (refundable) premium payment when applying.6 Moreover, the law’s language seems to tilt in the direction of using a presumptive condition list. However, insurers’ underwriting practices vary widely: any list is likely to include conditions that some insurers are willing to cover and omit some that could lead to a denial. So it would make sense to allow both routes to coverage: having a condition on a set list or denial by an insurer for a condition not on the list.

It is harder to say how the program should treat people who have been offered a substandard rate. Should someone who is offered coverage at 110 percent of standard be allowed into the pool, drawing federal subsidy dollars to obtain a slight premium discount? An alternative is to set a higher threshold, such as the 150 percent of standard used in the modeling in this analysis. But then someone who is offered a 150 percent rate would be bought down to 100 percent, while people offered a 145 percent rate would be left out. These perplexities are just one of the drawbacks of the law’s limiting the premium to standard rates.

One problem with relying on carrier decisions is that carriers have an increased incentive to turn down marginal cases. Of course this is already true in states with pools, but there is an offsetting incentive: the more people in a state’s pool, the higher the assessments on private insurers in the state. This countervailing incentive would not exist for the federally funded pools.

Other Eligibility Rules

Access to other coverage. While the law excludes people who had coverage within six months of applying, it does not exclude people who could obtain coverage elsewhere and have failed to do so. As noted earlier, a considerable number of people who might be medically uninsurable in the nongroup market do have access to other coverage. It might be reasonable to consider closing enrollment to people with access to employer coverage or people who could have taken up continuation coverage but did not. The HHS secretary also could require states that operate pools to screen for potential Medicaid and CHIP eligibility. Whether either measure would save very much is doubtful. People are unlikely to pass up employer coverage for the more costly coverage likely to be offered by PPACA pools, and few people who could afford pool premiums would qualify for Medicaid or CHIP.

State residence. Under the PPACA, eligibility extends to any U.S. citizen or legal resident meeting the pre-existing condition and coverage gap requirements. State pools commonly limit participation to people who have been resident in the state for a fixed period before applying. Should states be allowed to continue these rules under the new program? If not, what will prevent people in a state whose program has reached capacity from applying for coverage in some other state (or for the national program in a state that isn’t operating a federal pool)?

Medically eligible children. Despite ambiguities in statutory language, HHS and the insurance industry have agreed to interpret PPACA as immediately prohibiting denial of coverage or substandard rates for children on the basis of health risk. In theory, this would obviate the need to admit children to the high-risk pool. However, it appears that insurers could still refuse entire families, or perhaps could impose a higher premium on the entire family (without singling out any particular family member as the reason for the substandard rate). Unless these problems can be overcome, pools may need to be open to the very small number of potentially eligible children.

Underinsured. As noted previously, the NAIC model act would admit to a pool an applicant who could find some coverage in the nongroup market but not coverage ’substantially similar’ to the pool’s coverage. An example might be someone offered only a policy with a $10,000 deductible. (People offered only a high-deductible plan as a result of medical underwriting must be differentiated from people who choose a high deductible to obtain a lower premium.) It is not clear how common this practice is, but a case could certainly be made for admitting such individuals to the pool. There is an obvious equity problem raised by the requirement for a six-month coverage gap: people who already have low-value plans would be unable to shift. But the six-month rule raises the same equity issue with regard to people who have already been struggling to pay substandard premiums. Without this bar, the program could be swamped with current nongroup purchasers.

Benefits

Cost-sharing levels. The minimum benefit standards in the law—65 percent coverage of costs and a $5,900 out-of-pocket limit for an individual—might allow packages that expose enrollees to considerable expense. For a population with a risk ratio of 1.5 times standard and higher, a plan with a deductible of something like $3,250 and coinsurance of 20 percent up to the out-of-pocket limit would have been in compliance with the 65 percent rule in 2007.7 There would be many other ways of reaching the same target—a higher deductible plus fixed copayments, limitations on prescription drugs or other specific services, or other variants.

Cost sharing at this level would obviously preclude access to needed services for lower-income enrollees. On the other hand, for some enrollees even higher cost sharing would not be unsustainable. As noted earlier, 21 percent of the uninsured with high-cost chronic conditions had incomes above 400 percent of poverty. It could be argued that, for these enrollees, pool enrollment should serve as a form of catastrophic coverage, rather than as a way of facilitating access to routine care. If the program could use income-based cost sharing, hefty contributions from those who could afford them could reduce overall premiums. Savings in premium subsidies could then finance reduced cost sharing for lower-income enrollees. How far this model could be taken within the PPACA rules is uncertain. Arguably, the pool might be in compliance if it covered 65 percent of the aggregate expenses of its enrollees, but the proportion covered for individual members varied by income. Income-based cost sharing might be left as an option for individual states, many of which are already performing income determination for their state-funded pools. Adding an income-related feature to the federally operated pool might be more difficult. (PPACA provides for income-related cost sharing in exchange plans beginning in 2014, but the mechanisms for administering this have not yet been developed.)

Pre-existing condition exclusion. While it seems paradoxical for a high-risk pool to apply a pre-existing condition exclusion, this is a standard component of state programs, because of concerns about people jumping in and out of the pool to meet a one-time medical need. An example might be someone who needs knee surgery, joins the pool, and drops out after a month or two. Offering coverage without an exclusion is costly. A Maryland analysis of short-term enrollees with and without a six-month exclusion found that those without the exclusion cost about 40 percent more.8 With a $5-billion limit on funding, the prohibition of pre-existing condition exclusions in the federal pools is likely to significantly reduce the number of people who can be covered. Even if the adjustment authority in the law were read as allowing a modification of the rule, it would be in some respects counterproductive to admit someone to the pool because he or she has cancer, for example, and then deny coverage of treatment for six months.

There are alternatives to a strict exclusion that could still help control costs. The high-risk pool in Tennessee has experimented with a system under which enrollees can choose between a plan that covers 80 percent of costs after six months and one that covers 50 percent of costs immediately. Some costs, such as chemotherapy and radiation and maintenance prescription drugs, are covered regardless of the exclusion.9 In Maryland, subscribers pay a 50 percent premium surcharge to avoid a six-month exclusion. The surcharge is reduced to 10 percent for members below 200 percent of poverty and 30 percent for those between 200 percent and 300 percent of poverty.10 Another approach that could reduce short-term enrollee churning would be to establish a minimum enrollment period, similar to those imposed by mobile phone contracts, to assure that people with a one-time medical need would continue contributing to the system after that need was met. There could be a penalty for early termination, with an exception for people who become eligible for other coverage.

Premiums

Under the law, temporary high-risk pool premiums must be set at 100 percent of ’a standard rate for a standard population.’ Commonly, state pools develop a standard rate by looking at the rates charged by major nongroup carriers in the state for a benefit package comparable to the one offered by the pool. If comparable packages are not common in the state, the pool may need to take premiums from widely sold policies and actuarially adjust for benefit differences.

It should be emphasized that states are setting the standards by looking at (and adjusting) actual premiums charged by nongroup carriers. These carriers will often have a medical-loss ratio of 70 percent or less—meaning that 70 percent of the premium goes to pay claims and the rest to cover administration and profit. (PPACA requires nongroup carriers to raise their loss ratios to 80% by 2011 or issue rebates to consumers.) In state pools, the comparable ratio—claims as a share of combined premium and subsidy revenue—ranged from 85 percent to 99 percent in 2008, with a weighted average of 95 percent. This is partly because they do not incur some costs, such as marketing, and do not make a profit, but also because administrative costs are being measured against a very high claim volume. The state solicitation issued by HHS indicates that states should plan to limit administrative costs to 10 percent of claims. But this does not mean that a standard rate would have to assume the same level of administrative spending. The standard is a benchmark of what the private market would charge, not a projection of the pool’s own costs.

If the same methods were used for the temporary pools, rates could be quite high. Note that, in actuarial terms, the presence or absence of a pre-existing condition exclusion is a component of a benefit package and should be considered in establishing a standard rate. The correct standard rate for a pool that imposes no pre-existing condition exclusion should be considerably more than the standard rate for an otherwise comparable nongroup plan that imposes an exclusion. This, combined with the use of an administrative loading based on private nongroup market practices, might produce an average single rate of $600 or $700 a month for pool coverage in 2010—or a higher amount for older enrollees.

Setting premiums at this level would make the program affordable only for higher-income participants. Some lower-income people might participate but likely only those with the greatest medical needs. The PPACA language is vague enough that the HHS secretary or states might be able to bring rates down somewhat by deviating from the usual method of setting standard rates. The standard could be set using common nongroup rates without a correction for the lack of a pre-existing condition exclusion or other benefit differences. Administrative loading could be reduced to reflect the temporary pools’ actual administrative costs. But, of course, finding ways of reducing the premium paid by enrollees would simply raise per enrollee subsidy costs, speeding exhaustion of the available funds. In a sense, the decision about premium methodology is a choice between making the program affordable for more people for a shorter period or making it affordable for fewer people for a longer period.

Treatment of Existing State Programs

All but five states have some measures in place to assist high-risk individuals: regulation of issue and rating practices, high-risk pools, or both. Generally, states using both approaches have looser regulations that provide incomplete protection. For states already operating pools, how will the new temporary pool program, whether managed by the state or the federal government, fit around the existing program? For states that have instead opted for strict regulation of the nongroup market, what would be the effect of adding a new high-risk pool?

States with existing pools. In states already operating pools, the new federal pool will almost certainly be less costly for enrollees and will probably offer superior benefits—in particular, immediate coverage without a pre-existing condition exclusion. The six-month noncoverage rule means that current state pool enrollees will be trapped in their inferior arrangements, unless they are willing to accept a lapse in coverage. There doesn’t appear to be any way of correcting this inequity; even the broadest reading of the HHS secretary’s authority would not allow funds to be used to improve benefits for the currently insured.

Meanwhile, new applicants who can meet the six-month rule will have a strong incentive to choose the federal pool instead of the state pool, and states will have an incentive to steer them toward the federally funded pool. Texas, which has declined to operate a temporary federal pool, is already issuing a letter to state risk-pool applicants, informing them that the new federally operated pool may be available in July 2010 and will have no pre-existing condition exclusions and charge premiums at half the Texas rate (because the Texas pool uses 200% of the standard rate). The letter concludes, ’You should determine which risk pool program—state or federal—best serves your needs, based on your individual circumstances.’13

The maintenance-of-effort requirement is supposed to deter this kind of steering, but it applies only in states that contract to operate the federal pool. States that fail to do so, leaving the federal pool to be run by HHS, have no funding requirement. They could drop their existing pool or, more realistically, could freeze enrollment or at least limit enrollment to people not meeting federal pool eligibility rules. The potential for attrition in the existing pools is not trivial. While average duration of enrollment in state pools was 36 months in 2008, six states had average duration of 24 months or less.14 If most new enrollment in these states shifted to the federal pool, it could largely replace the state pools within two years. Even in states that are subject to maintenance of effort, the required funding commitment does not increase with inflation, so a state could comply while allowing some attrition in its current pool.

One possible way of assuring that federal funds expand coverage, instead of replacing state funds, is through the allocation formula. Although HHS has already indicated that the first year’s formula will be population based, there is nothing to prevent formulas for subsequent years from including some form of adjustment to reward states that maintain or increase enrollment in their own pools (or penalizing the reverse, though this seems self-defeating).

States with strict regulation. There are currently six states that require guaranteed issue by all carriers and allow no variation in rates by health status.15 While all of these states plan to set up some form of pool under the federal program, it is not clear what role a high-risk pool program could play. Carriers are already offering coverage at a standard rate to all applicants; the pool could be less costly only if it offered less generous coverage or possibly reduced administrative costs. While it appears that the HHS secretary is still required to establish a pool in these states, adding the pool might have destabilizing effects. Either the federal subsidies bring the pool’s rates below a true community rate, distorting competition, or the pool becomes simply another option with no apparent benefit.

This does not mean that there is no problem of uninsurance in these states. Nongroup premium rates tend to be higher than in other states, in part because there too few lower-risk enrollees to share the costs for the higher-risk participants. In the extreme case, New York, nongroup premiums averaged $6,630 in 2009’more than twice the national average.Is there some way that the newly available federal funding could help alleviate this problem?

One option would be to establish a pool only for a limited list of high-cost conditions. This pool could set an artificially low standard rate, drawing some people with the specified conditions out of the private nongroup market in the state. This could increase aggregate rates of insurance, because nongroup carriers would be able to offer lower rates to applicants who were ineligible for the federal pool. Still, it would be more efficient to get the federal dollars into the system without setting up a parallel insurance program—for example, simply by giving grants to the states to subsidize low-income enrollees or to provide reinsurance that could lower nongroup rates. But there is no apparent way of doing this within the legal framework of the program.

Administration of the program in non-contracting states. In the states that have chosen not to participate in the risk pool program, HHS appears to have three basic options: 1) operate through Medicare; 2) contract with the national Blue Cross arrangement that serves Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHBP) enrollees or with another national carrier; or 3) contract with private nonprofit entities in each state. The last seems least practical: if there were states where HHS could not find a contractor, it would have to use the Medicare or national carrier option as a backup. It would probably be more efficient to settle on one or the other for all non-participating states.

Under the Medicare option, Social Security offices would seem to be the logical place for accepting and processing applications (as under the Medicare Part D low-income subsidy program). Claims processing and other insurance functions could be performed by current Medicare intermediaries and carriers. As some observers have noted, providers might object to accepting low Medicare payment rates for pool enrollees. Pool rates could arbitrarily be set at some higher level (as would have been the case for the public plan included in the House health reform bill). But it is not clear that there would be any authority to compel Medicare-participating providers to accept risk-pool payment rates as payment in full. To prevent unlimited balance billing, contracts would have to be negotiated with these providers, an expensive and time-consuming process. Using Medicare as the coverage vehicle for pools also could raise political concerns; some might perceive this approach as a step toward a single-payer program.

The national carrier option might or might not be workable. There is no actual national Blue Cross Blue Shield plan. The program for federal employees is a long-standing ad hoc arrangement in which the regional Blue Cross Blue Shield plans have agreed to participate; it has no other clients. The local plans might sign on if the arrangement for the pools is as much like their current FEHBP contract as possible. Under FEHBP, the plans have no involvement with processing applications and enrollments or collecting premiums; these functions are performed by employing agencies.17 Some entity would be needed to perform these tasks. If the Blues are unwilling to contract, none of the other national plans in FEHBP, all ostensibly operated by employee associations, seem like likely candidates. There are some non-FEHBP carriers that offer national coverage to large employers; whether any one of these could actually serve as the carrier in every single state would need to be seen. Possibly HHS could select the Blues or another insurer as the carrier for most states and then negotiate contracts individually for states in which the national carrier is unable—or the local Blue Cross affiliate is unwilling—to provide coverage.

Treatment of Existing State Programs

T

his analysis has suggested a number of options for stretching the limited funds appropriated for the temporary national high-risk pool program, at the price of limiting access to the program or providing less comprehensive coverage. Even with these measures, it seems likely that—unless more funding is provided—the temporary pool program will rapidly reach capacity and have to establish a waiting list. This could leave hundreds of thousands of potential participants with serious medical problems unable to obtain coverage until the full set of reforms takes effect in 2014. It is not difficult to guess who will be waiting in line when the new exchanges open their doors on Jan. 2, 2014. The exchange plans may suffer considerable adverse selection’attracting a sicker-than-average population’at the outset. This will be compounded by the closing of the high-risk pools’both the federally funded pools and presumably most existing state pools. Most of their enrollees will go directly into the exchange.

Over time, premium subsidies and the individual mandate to have insurance may gradually bring a more representative population into the exchange plans. At the outset, however, they will have difficulty competing with nongroup insurers operating entirely outside the exchange. Although these plans will be subject to guaranteed-issue rules, they will have an existing, healthier enrollment base, and might be able to offer favorable rates, especially to people ineligible for the PPACA’s income-based subsidies.18

The law includes three mechanisms that take effect as the exchanges begin operation in 2014 that are intended to deal with this problem:

- Under a temporary reinsurance program, all issuers of coverage, including insurers and the administrators of self-insured employer plans, will pay an assessment into a reinsurance pool. The available funds will be paid out to nongroup insurers that enroll people with a high-risk medical condition; the HHS secretary is to develop a list of 50 to 100 such conditions. Assessments available for payout to insurers are to total $10 billion in 2014, $6 billion in 2015 and $4 billion in 2016, the program’s final year.19

- Also for the first three years, individual and small group insurers will be subject to a risk-corridor system. Those whose allowable claims costs are less than 97 percent of a target amount based on premium revenues will pay part of their profits into a pool; the pool will cover part of the losses of plans whose costs are more than 103 percent of the target amount.

- There will be a permanent risk-adjustment system for all individual and group health plans (other than self-insured employer plans and some grandfathered plans) in each state. Plans with a lower-risk population will make payments to plans with a higher-risk population. How risk is to be assessed and funds to be distributed is unspecified; the HHS secretary is to develop a method in consultation with states.

A full discussion of these provisions is outside the scope of this analysis, but each has some limitations that may reduce its potential for overcoming the selection problem. The risk- corridor system would provide some protection but would still leave insurers potentially exposed to considerable losses. For example, an insurer whose claims came in at 110 percent of the target amount would be paid 4.1 percent of the target amount, covering less than half its loss. An adequate risk-adjustment system for the non-Medicare population is likely to require huge amounts of new data collection and could take years to develop and calibrate.

Over the short term, the reinsurance program seems most likely to offer the kind of protection that might be needed to induce carriers to join the exchanges. The reinsurance program resembles a state high-risk pool in a number of respects. It is funded through assessments on insurers—except that the federal program also can assess self-insured employer plans, which states usually cannot reach except indirectly, through assessments on stop-loss carriers. It makes payments, comparable to a state pool’s premium subsidies, on behalf of people with conditions on a defined list. But, it also differs from high-risk pools in some ways, presenting possible problems. First, it may need to rely on reporting by insurers and could be subject to gaming if insurers assign patients to preferred diagnoses. It would apparently operate retrospectively, leaving insurers at risk until they receive unpredictable future payments. Finally, there is no way of knowing whether the budgeted amounts—especially for the third year—will be sufficient to cover the costs for the high-risk population.

It may be worth considering whether it would be preferable to continue the high-risk pool program for some time after the establishment of the exchanges, or perhaps to allow states to determine whether the new revenues yielded via the all-issuer assessments should be used for reinsurance, a risk-pool arrangement or both. There are obvious drawbacks to risk pools: they may lead insurers to continue the costly practice of examining applicants’ medical history, and they do nothing to compensate insurers for high-cost problems that emerge after enrollment, as reinsurance does. But there may be advantages as well. Insurers may be more willing to enter the exchange market if they can temporarily divert applicants with high predictable risk. A pool for people with specific conditions might also promote programs to improve management of those conditions.

Another option would be to continue risk pools solely for those who were enrolled in them on Jan. 1, 2014, and who chose to remain in them. This would at least prevent the sudden dumping of half a million high-cost people into the new exchange plans. Reinsurance payments for those with specified conditions could partially replace existing premium subsidies, but additional assessments or other revenue would probably be needed. The PPACA reinsurance provisions include language on coordination between the reinsurance program and state high-risk pools that might be interpreted as permitting this use of reinsurance funds, but the intent is unclear.20

The insurance markets—in and out of the exchanges—that arise in states in 2014 will not all be the same, because of differences in income distribution, current availability of employer-sponsored coverage and many other factors’not least, each state’s own past efforts to fix the nongroup market. Until a fully workable national risk-adjustment system can be implemented, there may be a case for allowing each state to develop its own approaches to the problems of risk selection and risk distribution.

Notes

1. HHS, “Sebelius Continues Work to Implement Health Reform, Announces First Steps to Establish Temporary High Risk Pool Program,” News Release (April 2, 2010); The state solicitation is available at www.hhs.gov/ociio/Documents/state_solicitation.pdf.

2. MEPS shows 39.3 million nonelderly people with no insurance at any time in 2007. This number should correspond to estimates provided by the Current Population Survey (CPS), which identifies people without insurance for an entire calendar year. However, CPS shows 44.9 million nonelderly people with no health insurance in 2007. For a discussion of some of the reasons that MEPS and CPS estimates differ, see www.aspe.hhs.gov/health/Reports/uninsur3.htm.

3. See www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp.

4. Ryan, Jennifer, The Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP): The Fundamentals, National Health Policy Forum, Washington, D.C. (April 2009).

5. Foster, Richard, ’Estimated Financial Effects of the ’Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,’ as passed by the Senate on Dec. 24, 2009,’ CMS, Baltimore, Md. (Jan. 8, 2010).

6. Pollitz, Karen, Issues for Structuring Interim High-Risk Pools, Kaiser Family Foundation, Washington, D.C. (January 2010).

7. The modeling for this estimate uses an out-of-pocket limit of $5,500; this is the limit that would have applied if the PPACA rules had been in effect in 2007.

8. Popper, Richard, and Frank Yeager, Maryland Health Insurance Plan: Analysis of Preexisting Condition Exclusion ’Buy Down’ Rider (September 2009), available at www.naschip.org/Arlington/popperyaeger.pdf.

9. Hilley, David, Coverage Options for Pre-Existing Conditions in State High Risk Pools ’ AccessTN benefit design, (September 2009), available at www.naschip.org/Arlington/Hilley.pdf.

10. Popper and Yeager (September 2009).

11. Leif, Elizabeth, Standard Risk Rates (Oct. 16, 2008), available at www.naschip.org/Savannah/Presentations/Liz%20Leif/Standard%20Risk%20Rates.pdf.

12. U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), Health Insurance: Enrollment, Benefits, Funding, and Other Characteristics of State High-Risk Health Insurance Pools, letter to congressional requesters, Washington, D.C. (July 2009)(GAO-09-730-R).

13. Texas Health Insurance Pool, New Temporary Federal High Risk Pool Program Notice (May 3, 2010), available at www.txhealthpool.org/New_Temp_Federal_Pool_Notice_REV_05-03-2010.pdf.

14. GAO (July 2009).

15. They are Maine, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Vermont and Washington, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation’s statehealthfacts.org. Three other states, Idaho, Oregon and Utah, have fairly tight rules but not enough that there would be no role for a pool.

16. America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), Individual Health Insurance 2009, Washington, D.C. (2009).

17. Or, in the case of annuitants, by the Office of Personnel Management.

18. Insurers that operate both in and out of the exchange would not benefit from this risk selection, because PPACA would require them to treat all their enrollees, exchange and non-exchange, as a single risk pool.

19. There are additional assessments that will not be used for reinsurance but will instead go into the Treasury general fund.

20. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Public Law No. 111-148), Section 1341(d).

Data Source

People are classed as having a chronic condition if they reported, at any time during 2007, one of the conditions defined as chronic in the HCUP system. HCUP uses five-digit ICD-9 codes to classify conditions as chronic or nonchronic. MEPS public-use data provide only higher-level three-digit codes. For the estimates in this analysis, three-digit codes are classed as chronic if they include any five-digit code with a chronic classification. As a result, these estimates show a slightly higher prevalence of chronic illness than corresponding AHRQ estimates.

To identify people with high-cost conditions, a standard premium rate was first established for each of the four age classes used. The rates are based on private insurance payments (not total spending) for MEPS respondents who had employer coverage throughout 2007. Data on people with employer, rather than nongroup, coverage were used because: 1) employer plans are more comprehensive, and spending will reflect the full scope of likely utilization by people with and without health problems; and 2) nongroup data are affected by medical underwriting, which excludes the very people whose utilization is of interest. The resulting ’rates’ (which include only claims costs, not administration) for the age classes were then compressed to comply with the 4:1 limit in the PPACA risk-pool provisions.

A condition is defined as high cost if average claims cost for people with that condition is at least 150 percent of the standard rate for their age group. So dropsy is a high-cost condition if children with dropsy have average costs of $1,017 x 1.5, adults aged 19-34 with dropsy have average costs of $2,035 x 1.5, and so on. This very simple method ignores interactions: some combinations of two or more lower-cost conditions undoubtedly result in high average costs, but these were not identified.

A true standard rate in a given market is a rate after whatever underwriting is common in that market. Properly, the