Despite heightened employer interest in workplace clinics as a cost-containment tool, only 4 percent of American families in 2010 reported visiting a workplace clinic in the previous year—the same proportion as in 2007, according to a national study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). The severe 2007-09 recession likely dampened employer investment in workplace clinics, and some workers likely lost access to clinics because of job layoffs. Workplace clinics are concentrated among large, self-insured employers, so only a subset of families has access to these resources. Among families most likely to have access—those with ties to large firms and government employers—clinic use was higher at nearly 11 percent in 2010. Most experts believe workplace clinics can best achieve cost savings through better prevention and early diagnosis of chronic conditions. However, the study found that among clinic users, the most commonly sought services were vaccinations and other minor, routine services. Nearly seven in 10 people cited convenience as a major reason for choosing a workplace clinic over other care settings, and four in 10 cited lower costs. Workplace clinics are typically only viable for large employers with low employee turnover and high concentrations of workers, which means they are unlikely to provide a broad solution for controlling health care spending or improving care delivery.

- Despite Employer Interest, Workplace Clinic Use Low

- Recession Fallout on Workplace Clinics

- Clinic Use Varies by Industry

- Most Visits for Minor, Routine Care

- Convenience and Cost Key to Clinic Use

- Usual Source of Care and Workplace Clinic Use

- Implications

- Notes

- Data Source

Despite Employer Interest, Workplace Clinic Use Low

As employers continue to grapple with spiraling health care costs, more large firms are considering workplace clinics as a tool to contain spending. Although workplace clinics have received increased attention in recent years, they are not a new phenomenon. Employers have offered onsite health care for decades, traditionally with a focus on occupational health or routine services, such as treatment of sore throats and runny noses.

What distinguishes many emerging workplace clinics is a shift toward primary care, preventive services and wellness offerings.1 By incorporating these services, employers hope to generate savings on overall medical costs. In the short term, a key employer objective is to exert greater control over high-cost services, such as specialist referrals, brand-name prescriptions, emergency department visits and avoidable hospitalizations. In the long run, improving population health by preventing and managing chronic conditions is a major objective.2

Findings from recent employer surveys confirm that employer interest has increased, as the share of large employers reporting plans to implement an onsite clinic over the next two years doubled between 2007 and 2011, from 6 percent to 12 percent.3 Moreover, the number and size of vendors specializing in operating onsite clinics have grown in recent years.4

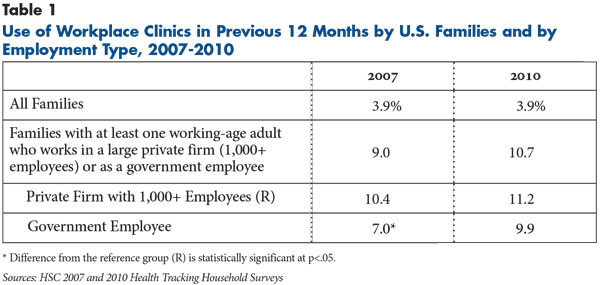

Despite evidence of high interest among large employers, use of workplace clinics remains low. In 2010, only 4 percent of all American families reported having at least one member who used a workplace clinic in the previous year, according to findings from HSC’s nationally representative 2010 Health Tracking Household Survey (see Data Source). This estimate was unchanged from 2007 (see Table 1).

The low use is not surprising, given that only a subset of Americans has access to workplace clinics. To better reflect that only some families have access to workplace clinics, this study focused on the subset of families with at least one working-age adult, aged 18-64, employed by a private firm with at least 1,000 workers or by a government employer. After narrowing the analysis to this subgroup, nearly 11 percent of such families in 2010 reported visiting a workplace clinic during the past year—roughly the same proportion as in 2007.

Recession Fallout on Workplace Clinics

Increased unemployment rates between 2007 and 2010 likely contributed to the flat trend in workplace clinic use.5 Recent research indicates that large employers—1,000 or more workers—disproportionately shed workers and reduce hiring during recessions.6 This pattern held true during the 2007-09 recession, and, as a result, a substantial number of people laid off by large employers likely lost access to workplace clinics. Indeed, 12 of the 25 companies with the highest number of layoffs between 2007 and 2010 offered workplace clinics at the time.7

Also, financial pressures caused some employers to delay or cancel plans to open clinics and other employers with existing clinics to scale down or even shutter their clinics.8 Several employer surveys confirm that the prevalence of workplace clinics among large employers remained unchanged (at about 25%) over this period.9

Clinic Use Varies by Industry

Workplace clinic use was highest among families with workers employed in the manufacturing sector. Nearly 17 percent of such families reported using a workplace clinic in the previous year, according to estimates from combined 2007 and 2010 survey data (findings not shown). This reflects the historical and ongoing importance of onsite clinics to manufacturers, which commonly rely on clinics to treat work-related injuries and other occupational health problems.

More than 11 percent of families with workers in public administration and a similar share of families with ties to the services sector used a clinic in the past year. At the other end of the spectrum were families employed in the transportation or public utilities sector (3.4%) or in wholesale or retail trade (3.4%).

Most Visits for Minor, Routine Care

As previously noted, research shows that increasingly employers are offering some combination of preventive, wellness, primary care and disease management services in workplace clinics. Experts believe this approach holds the greatest potential for meaningful cost containment by altering provider practice patterns and improving underlying population health. Workplace clinics that offer primary care can try to encourage more efficient care delivery by monitoring specialist referrals, tests and procedures; substituting generic prescribing for brand-name prescribing; and otherwise streamlining and standardizing primary care relative to community-based practices. Improving population health typically requires a multi-pronged approach aimed at both keeping healthy people healthy and helping people who already have chronic conditions better manage their conditions.10

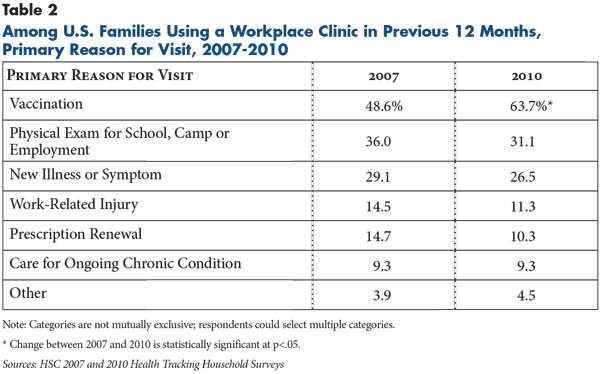

Even as employers focused on primary care and wellness offerings in workplace clinics in recent years, the services most often sought by clinic users were for minor, routine care (see Table 2). When asked the primary purpose of their clinic visits, 63.7 percent of survey respondents in 2010 cited vaccinations—by far the highest prevalence for any clinic service. From 2007 to 2010, the proportion of people citing vaccinations increased by 15.1 percentage points—a surge in demand that may be related to the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic.11 This phenomenon was not limited to workplace clinics and reflects a more general trend of rising vaccination rates during this period that also impacted other care settings, such as retail clinics.12

Despite widespread employer recognition of the importance of ongoing chronic care, use of workplace clinics for this purpose appears limited. Fewer than one in 10 clinic users in 2010 cited ongoing care of chronic conditions as the primary purpose for their visits unchanged from 2007 and far lower than the prevalence of chronic conditions in the workforces of most employers.13

Two important caveats should be noted about these results. First, a single family member answered questions about clinic use and reasons for visits on behalf of all family members, which may impact reliability. Moreover, because the survey asked clinic users only for the primary purpose of their most recent visit, estimates may not capture the full extent of the care patients received.

Previous research has shown that, in workplace clinics providing primary care and wellness services, clinicians typically use any clinic visit—including those for minor, routine care—as an opportunity to address broader aspects of a patient’s health.14 For instance, employees who go to a clinic with a sprained ankle or a sore throat would undergo blood pressure checks and other screenings at a minimum. Consequently, services such as vaccinations, physical exams—cited by 31 percent of clinic users—or treatment of new illnesses or symptoms—cited by 26 percent—all can provide opportunities for clinicians to identify health issues beyond the primary reason for the visit.

Convenience and Cost Key to Clinic Use

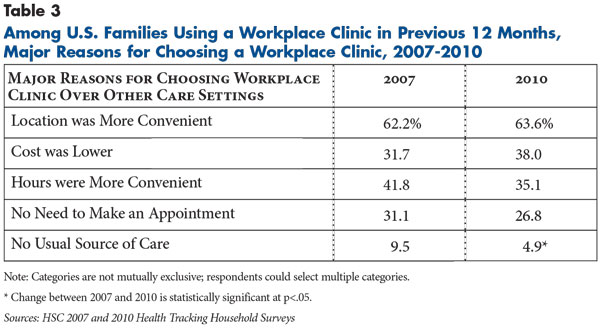

In addition to the primary purpose of the visit, users were asked why they chose a workplace clinic over other care settings, such as a physician’s office. By far the most common response (63.6%) was that the location was more convenient (see Table 3). Thirty-five percent noted that clinic hours were more convenient, and 27 percent cited not having to make an appointment. Overall, about seven in 10 clinic users cited at least one of these three convenience factors as a reason for choosing a workplace clinic (findings not shown).

Affordability also was a major concern among clinic users. Nearly four in 10 clinic users cited lower cost as motivation for choosing a workplace clinic over another source of care. This aligns with indications that employers may offer financial incentives to encourage clinic use.15 Often, employers will structure their benefits so that out-of-pocket cost sharing for clinic visits is lower than for community-based visits—for instance, $10- or $15-dollar differentials in required copayments are common among employers looking to incentivize workplace clinic use. Sometimes, cost sharing is waived altogether for clinic visits. As some employers shift toward higher out-of-pocket cost sharing for employees, clinics may become even more appealing in these cases.

Usual Source of Care and Workplace Clinic Use

People with access to workplace clinics often have regular, community-based providers. Therefore, it is important to understand how clinics interact with patients’ existing sources of care, especially since there are concerns that onsite clinics could increase care fragmentation by encouraging patients to seek care in multiple settings. On the one hand, having a usual source of care in the community other than an emergency department may lessen the need for care in other settings. On the other hand, community-based providers that can coordinate care across multiple settings may facilitate patients seeking supplementary care at workplace clinics.

In 2010, families with a usual source of care were significantly more likely to have used a clinic in the previous year compared to families without a usual source of care—12.2 percent vs. 7.5 percent (findings not shown). One possible explanation is that people with a usual source of care may be more connected to the health system and more aware of available resources. Or, they may have more health care needs and, therefore, seek more services across multiple settings. Another possibility is that some respondents might consider the workplace clinic itself to be their usual source of care, though this is likely to impact only a small number of cases.

Implications

Use of workplace clinics by American families remained low between 2007 and 2010, even among those with connections to employers most likely to offer clinics. On a broader scale, use of workplace clinics is low in part because only a small subset of the population has access to them. According to the 2010 Health Tracking Survey, while 63 percent of Americans are members of working families, only 15 percent of the population is directly employed by large firms or the government and only a minority of these employers has clinics in place. However, as the economy recovers and more companies initiate or revisit plans to offer clinics, the number of Americans with access to these resources may soon begin to grow.

Even as more employers implement workplace clinics, their reach is largely limited to employees of large firms with low turnover and highly concentrated workforces. Therefore, while clinics may be valuable tools for controlling costs and improving care for some segments of the population, they are not likely to provide a broad solution to rising costs. Nevertheless, clinics may have some potential to serve as testing grounds for innovations in care delivery and coordination that could have impacts beyond individual employers.

Notes

1. According to a recent employer survey, in 2010, 15 percent of employers with at least 500 employees had primary care clinics onsite—up from 11 percent in 2009—and another 10 percent were considering establishing such clinics over the next two years. See Hess, Corrinne, “Insurance Company Planning Clinics,” The Business Journal, Milwaukee, Wis. (May 20, 2011).

2. Tu, Ha T., Ellyn R. Boukus and Genna R. Cohen, Workplace Clinics: A Sign of Growing Employer Interest in Wellness, Research Brief No. 17, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (December 2010).

3. Towers Watson, New York, N.Y., and National Business Group on Health, Washington, D.C., Shaping Health Care Strategy in a Post-Reform Environment: 16th Annual Towers Watson/National Business Group on Health Employer Survey on Purchasing Value in Health Care (March 2011); Watson Wyatt, New York, N.Y., and National Business Group on Health, Washington, D.C., Dashboard for Success: How Best Performers Do It: 12th Annual National Business Group on Health/Watson Wyatt Survey Report (February 2007).

4. Tanweer, Anissa, “More Firms Opening On-site Clinics,” Arizona Daily Star (Jan. 1, 2012).

5. In December 2007, the national unemployment rate was 5.0 percent. At the end of the recession, in June 2009, it was 9.5 percent. The unemployment rate peaked at 10.0 percent in October 2009. See U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, BLS Spotlight on Statistics: The Recession of 2007-2009, Washington, D.C. (February 2012).

6. Moscarini, Giuseppe, and Fabien Postel-Vinay, Large Employers are More Cyclically Sensitive, Working Paper No. 14740, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Mass. (February 2009).

7. Eight of the top 25 so-called “layoff kings” had onsite clinics providing primary care at some point during 2007-2010. Another three offered occupational health services onsite and one had a clinic devoted to wellness. See McIntyre, Douglas, “The Layoff Kings: The 25 Companies Responsible for 700,000 Lost Jobs,” Daily Finance (Aug. 18, 2010).

8. Vesely, Rebecca, “On- and Near-site Clinic Slowdown Could Hurt Access: AAFP President,” Modern Physician (Jan. 12, 2009).

9. About a quarter of employers with at least 1,000 workers reported having a workplace clinic each year from 2007-2011. See Towers Watson/National Business Group on Health (2011); and Watson Wyatt/National Business Group on Health (2007).

10. Edington, Dee W., Zero Trends: Health As a Serious Economic Strategy, University of Michigan Health Management Research Center, Ann Arbor, Mich. (2009).

11. McNeil, Donald G., Jr., “Nation is Facing Vaccine Shortage for Seasonal Flu,” The New York Times (Nov. 4, 2009).

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Final Estimates for 2009-10 Seasonal Influenza and Influenza A (H1N1) 2009 Monovalent Vaccination Coverage—United States, August 2009 through May 2010; and Uscher-Pines, Lori, et al., “Growth of Retail Clinics in Vaccination Delivery in the U.S.,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Vol. 43, No. 1 (July 2012).

13. Edington (2009).

14. Tu, et al. (2010).

15. Tu, et al. (2010).

Data Source

This Research Brief presents findings from the Center for Studying Health System Change 2007 and 2010 Health Tracking Household Surveys. Both surveys use nationally representative samples of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population. For the first time, the 2010 survey included a cell phone sample because of declining percentages of households with landline phones. Sample sizes included about 18,000 people for the 2007 and about 17,000 people for the 2010 survey. Response rates for the surveys were 43 percent in 2007 and 46 and 29 percent, respectively, for the landline and cell phone samples in 2010. Population weights adjust for probability of selection and differences in nonresponse based on age, sex, race or ethnicity, and education. The weights adjust also for the increased probability of selection in cases of households using both landline and cell phones. The 2007 and 2010 surveys were based on a stratified random sample of the nation. Standard errors account for the complex sample design of the surveys. Questionnaire design, survey administration and the question wording of all measures in this study were similar across surveys.

For each surveyed family, the primary family respondent was asked: “Have you [or names of other family members] ever used an onsite health clinic at your or [Spouse’s] workplace?” Respondents who answered yes were then asked: “Have you [or names of other family members] used an onsite health clinic at a workplace during the past 12 months?” Respondents who answered yes to this question were then asked about services obtained during clinic visits and reasons for choosing workplace clinics over other care settings.

All estimates reported in this study are family-level, not person-level, estimates, because respondents were not asked which family members received workplace clinic services. Most estimates presented in this study were based on the subset of families with at least one working-age adult, aged 18-64, employed by a private firm with at least 1,000 workers or by a government employer. Sample sizes for this subset of families with workplace clinic visits in the past year were 260 in 2007 and 259 in 2010. Individual characteristics—such as having a usual source of care and industry type—were ascribed to the family based on the member who was identified as the most likely to have access to workplace clinic—i.e., the working-age adult employed by a large firm or a government employer.