Introduction

Since its passage in 2010, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has introduced a series of health care financing and delivery reforms to expand coverage, invest in health care infrastructure, and implement changes to improve quality and costs. In 2014, the ACA’s coverage expansion began in Michigan through the launches of the health insurance marketplaces on January 1 and the Healthy Michigan Plan (Michigan’s Medicaid expansion program) on April 1. These programs have contributed to sharp reductions in the number of uninsured Michigan residents.[1]

The ACA coverage expansion has also had outsized effects on the health care safety net, particularly for federally qualified health centers (FQHCs). These centers are supported through federal grants to deliver services in impoverished and high-need areas, and have traditionally been a major source of medical services for the uninsured. FQHCs have been expected to financially benefit under the ACA from serving more patients with health insurance. In addition, the ACA supported grants to local organizations to bolster the safety net, the health care workforce, public health infrastructure, and other quality improvement programs. This brief will describe the effects of the ACA on the safety net in Detroit, with a focus on the experiences of the city’s FQHC providers.

Key Findings

- Detroit-based organizations have received more than $100 million in federal grant funding supported by the ACA and subsequent legislation to expand delivery capacity, train new health care workers, and develop other programs.

- The number of patients and patient visits at FQHCs in Detroit increased by over 6% from 2013 to 2014, and the number of uninsured patients decreased by over 30% as the ACA’s coverage expansion took effect.

- Detroit FQHC patients tend to be poorer and are more likely to be racial minorities than other FQHC patients in Michigan. The characteristics of FQHC patients in Detroit were relatively stable from 2013 to 2014.

- The number of health care providers (physicians, nurses, physician assistants, etc.) employed directly by FQHCs grew by over 21% from 2013 to 2014 as FQHCs prepared to serve more patients. As FQHCs adjust to the new environment under the ACA, many are working to develop new strategies to serve unmet patient needs, particularly in areas related to behavioral health, oral health, substance use, and transportation.

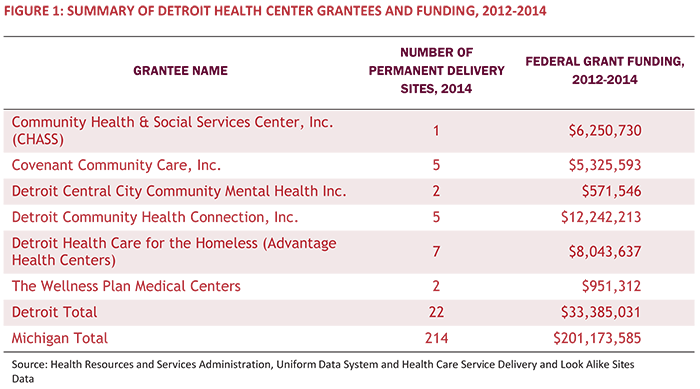

Health Centers in Detroit

In 2014, there were 214 permanent FQHC delivery sites in Michigan.[2] Within the City of Detroit, there were six FQHC systems operating 22 permanent health care delivery sites (Figure 1). Over 85,000 patients received care at an FQHC delivery site in Detroit in 2014, representing 14% of all FQHC patients served in Michigan that year. Detroit FQHCs operate 10.3% of the delivery sites in Michigan, but were awarded 16.6% of federal grants ($33.4 million) that went to Michigan between 2012 and 2014.

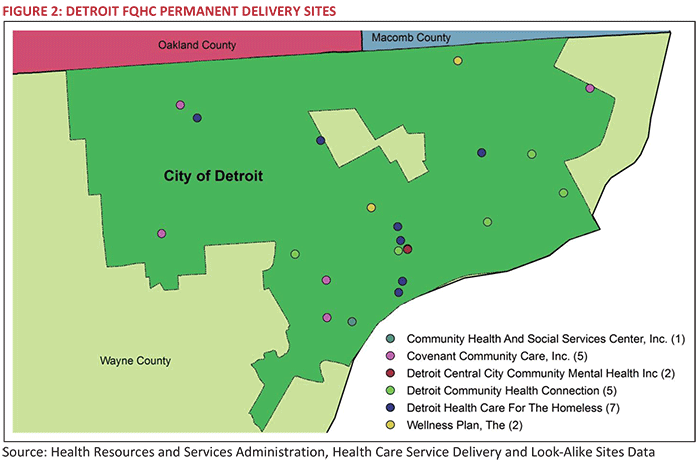

About one-third of FQHC delivery sites in Detroit are located in the Downtown and Midtown neighborhoods, with the others located in the West, Southwest and East neighborhoods. Detroit Health Care for the Homeless (which operates as Advantage Health Centers) has the most delivery sites in Detroit, located primarily in the downtown area. Other FQHCs, such as Covenant Community Care, Inc., are located in neighborhoods outside downtown Detroit (Figure 2).

ACA Coverage Expansion

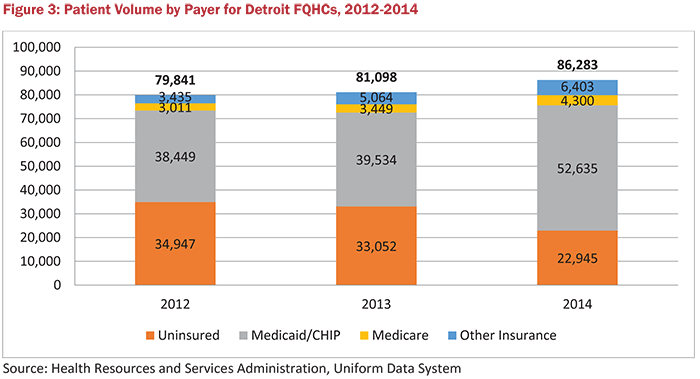

From 2013 to 2014, the number of patients served by FQHCs in Detroit increased by 6.4% (about 5,200 additional patients), much larger than the previous annual increase of 1.6% (about 1,300 additional patients) from 2012 to 2013. A substantial number of FQHC patients became eligible for insurance in 2014, primarily through the Healthy Michigan Plan (Michigan’s Medicaid expansion program). As a result, the number of uninsured patients served by Detroit FQHCs dropped by 30.6%—or by about 10,000 patients—in 2014, and the number of patients with Medicaid, including Healthy Michigan, or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) increased by 33.1% (by more than 13,000 patients). There were also more patients with Medicare and private insurance as well, but together, they comprised only 12.4% of total patients in 2014 (Figure 3).

Enrollment in the Healthy Michigan Plan did not begin until April 1, 2014, so there is potential for further reductions in the number of uninsured patients after 2014. However, despite the coverage expansion, a large number of patients at FQHCs may remain uninsured, in part due to the eligibility requirements for immigrants. Immigrants must be legal residents for at least five years or another qualified status (such as refugee status) before they are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP.[3] Unauthorized immigrants are neither eligible for Medicaid, CHIP, nor financial assistance through the health insurance marketplace.

FQHC Patient Population

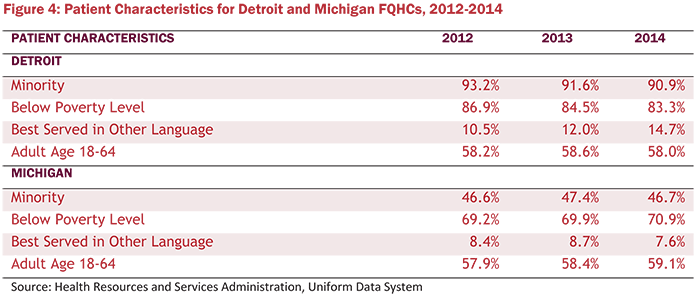

The population served by Detroit FQHCs has certain characteristic differences from that served by other FQHCs in Michigan. In Detroit, FQHC patients are almost twice as likely to be from a racial or ethnic minority group and are more likely to be below the federal poverty level (income of $11,670 for a single person and $23,850 for a family of four in 2014). In 2014, the share of Detroit FQHC patients who were best served in a language other than English was almost twice the statewide rate.

Between 2012 and 2014, the demographic characteristics of the patient populations served by Michigan and Detroit FQHCs were mostly unchanged. Detroit FQHCs experienced an increase in the share of patients best served in a language other than English and a slight decrease in the share of patients below the federal poverty level. However, the share of non-elderly adults, which is the subgroup most affected by the ACA coverage expansion, was almost unchanged (Figure 4). Between 2013 and 2014, most FQHCs experienced a greater change in the payer mix of their patient population than a change in their demographics.

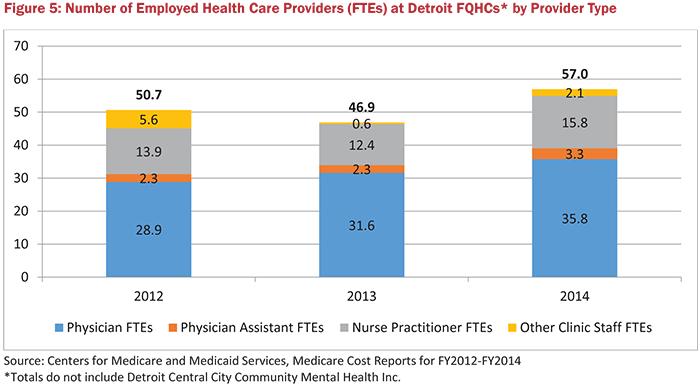

FQHC Workforce and Productivity

Many FQHCs in Detroit increased their workforce capacity to meet the growing needs of their community. From 2013 to 2014, the number of directly employed health care providers (physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, etc.) increased by 21.5% (Figure 5). These provider workforce increases came primarily from additional physicians and nurse practitioners. Along with directly employed health care providers, some FQHC systems have agreements with large health systems in Detroit that allow health system physicians to practice at FQHC delivery sites. FQHCs also partner with local universities to run residency and training programs at their centers for providers, such as physicians, nurses, dentists and social workers.

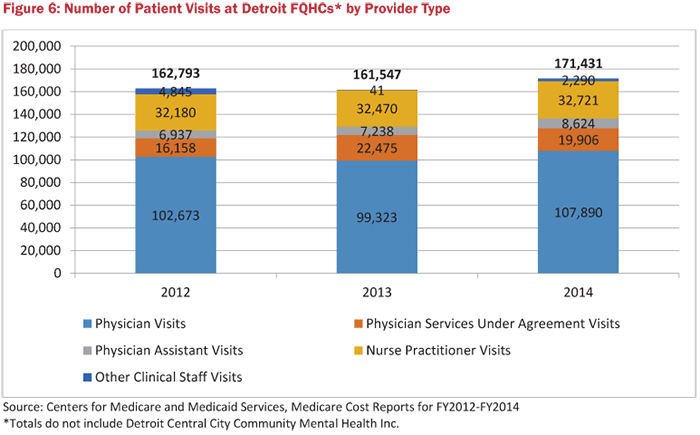

In 2014, FQHCs experienced an increase in the number of visits at their delivery sites. From 2013 to 2014, the volume of patient visits to FQHC delivery sites increased by 6.1%, about the same increase as the number of patients served (Figure 6). Providers who were directly employed by a FQHC provided the most care to patients. More visits were performed by directly-employed physicians and physician assistants in 2014 than 2013, while FQHCs had fewer services performed by physicians who work under agreement with a health system, rather than direct employment.

Other Changes Experienced by FQHCs

Based on our interviews with FQHC leaders in Detroit, FQHCs had mixed expectations of the magnitude of the increase in new patients that would seek services at FQHCs in 2014. Some leaders expected a greater increase in patient volume than their FQHC has experienced to date, while others had expectations that were more similar to the modest increase that has actually occurred. While it is difficult to verify, FQHCs believe that they have not seen a greater increase in patient volumes due to some newly insured FQHC patients relocating to other providers who would not previously see uninsured patients. This loss of patients offset some of the increase in new patients seeking services at FQHCs.

FQHC leaders we interviewed expect patient volume to increase further in 2015 and beyond with continued outreach and enrollment efforts, and time after the launch of the Healthy Michigan Plan. To prepare to serve more patients with Medicaid coverage, FQHCs had to expand their billing capacity and ensure their physicians were credentialed with each of the Medicaid managed care plans operating in Detroit.

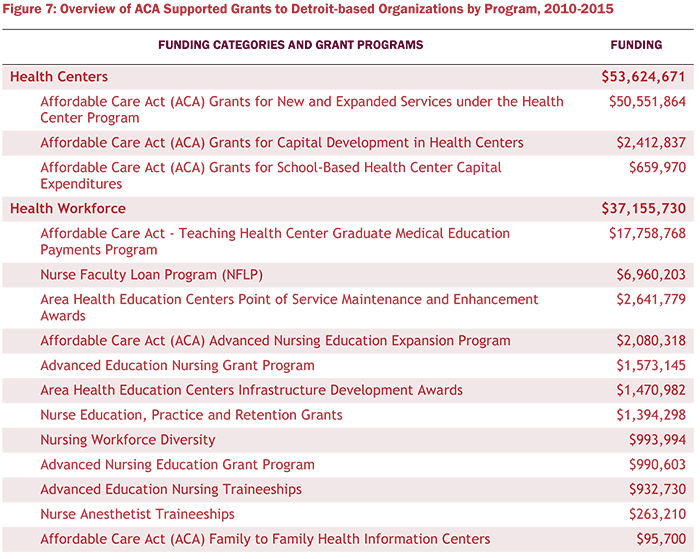

ACA Grant Funding Awarded to Detroit

Since March 2010, the ACA and subsequent legislation has included mandatory appropriations to support federal grant programs to expand access to care, implement broad private insurance reforms, and enhance the public health infrastructure.[4] During the 2010-2015 federal fiscal years, $101.7 million in grants were awarded directly to Detroit-based organizations (Figure 7).

The largest pool of the $101.7 million in ACA-supported funding went to FQHCs in Detroit to support new and expanded services. A large portion of other funding went to support workforce training programs. These totals include only grants awarded directly to organizations in Detroit and do not include awards to state agencies and other organizations that were then dispersed to programs in Detroit. Therefore, these totals are likely underestimates of ACA funding for Detroit.

Types of Funding Awarded

In order to administer new grant programs, the ACA included mandatory funding in several categories:[5]

- Community-based prevention: Includes a series of programs to improve public health infrastructure. The primary source of funding for these programs is the Prevention and Public Health Fund (PPHF).[6]

- Health Centers and the National Health Service Corps: Includes funding for FQHCs, the National Health Service Corps (NHSC), and school-based health centers. Much of these grants focus on providing care in underserved areas.

- Health workforce: Includes a series of programs to enhance capacity of the primary care workforce.

- Long-term care: Includes grant programs to support coordinated long-term care services.

- Market reform: Includes a series of grants that helped states reform their private insurance markets and prepare for the launch of health insurance marketplaces.

- Maternal and child health: Includes several grant programs targeted to serve at-risk families and prevent teenage pregnancy.

- Medicaid & CHIP: Includes grant programs focused on the health of enrollees in Medicaid and CHIP.

- Medicare: Includes a series of programs funded by the ACA to boost the effectiveness and efficiency of Medicare.

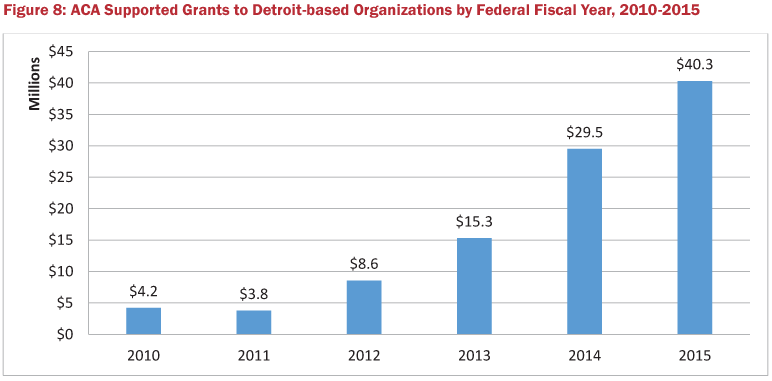

Growth in ACA Grant Funding

With the exception of the 2011 federal fiscal year, ACA grant funding awarded directly to Detroit-based organizations has increased every year since the ACA became law in March 2010 (Figure 8). In FY2015, Detroit organizations received $40.3 million in funding, an increase of more than 36% from the previous year.

How Federal Grant Funds Changed FQHC Capacity and Overall Operations

Grant funding from the ACA and other federal sources has been very important to FQHCs to expand and develop new capabilities. FQHC leaders each mentioned that federal grant funding was critical to their outreach and enrollment activities to get newly eligible patients health insurance coverage. For example, one FQHC created a drop-in office where residents could seek enrollment assistance without an appointment.

FQHC leaders also cited the importance of capital funding from the federal government to purchase new equipment (e.g., X-ray and ultrasound machines, and dental chairs). Federal funding was also important to expand their workforce to offer new services. For example, one FQHC received a federal behavioral health grant that allowed them to expand services to support behavioral health specialists on-site. According to FQHC leaders, federal funding was also critical to being able to implement certain quality improvement programs, such as developing the care coordination capacity to be designated as a patient-centered medical home (PCMH) and to meet federal meaningful use requirements with their electronic health record system.

Future Changes, Challenges, and Opportunities

According to one FQHC leader in Detroit, the ACA and coverage expansion has been “a blessing in the community…and a challenge in ways we could not imagine.” FQHCs played a major role in outreach and enrollment for Healthy Michigan Plan, which resulted in thousands of patients gaining coverage. With more insured patients, FQHCs reported improvements in referring patients to specialists who would see them. However, expanded coverage brought billing and administrative complexities that many FQHCs did not anticipate, including re-enrolling patients in the Healthy Michigan Plan and educating newly-insured patients about how to use their health coverage, which differs from the traditional Medicaid program. FQHCs still face issues of interoperability and reliability of their electronic health records, affecting their ability to communicate and coordinate care with partner organizations.

As newly-insured patients are able to access a wider range of services, another ongoing challenge for FQHCs is recruiting and retaining a strong workforce to meet the needs of the patient population. FQHCs continue to face challenges in providing competitive salaries for providers and administrative staff, and providing support to minimize provider burnout. For many FQHCs, particularly in urban settings such as Detroit, overcoming these challenges is largely dependent on partnerships with health systems and universities to recruit and retain a workforce and build local capacity across providers to meet the needs of the safety net population.

Opportunities to Help Satisfy Unmet Patient Needs

While the ACA was pivotal in expanding coverage for patients and the scope of services provided at FQHCs in Detroit, many patients still face barriers to necessary care. One of the most common barriers patients continue to face is transportation to a health center, particularly for urgent care services. For patients seen at FQHCs, oral health, vision, and substance use care services are among the greatest needs. Access to behavioral health services continues to be a challenge for immigrant patients, many of whom remain ineligible for coverage, due to the shortage of behavioral health providers who speak another language or will see uninsured patients.

In Detroit, FQHCs are developing strategies to meet the needs of their patient populations and dedicate more time toward direct patient care, offer more specialty services, and address broader unmet needs. For example, some FQHCs are implementing centralized scheduling, outsourcing billing operations, or increasing workforce to improve patient care, such as hiring scribes to assist with provider documentation.

FQHCs are also expanding hours and providing a wider variety of care within their centers, such as behavioral health, dental, and pharmaceutical services. To address more of the population’s overall needs, FQHCs are looking to offer transportation services or creating new partnerships to address broader issues, such as homelessness. How the health care safety net will continue to evolve to serve patients will be worth further examination as ACA implementation continues.

Conclusion

The Affordable Care Act has had significant effects on the U.S. health care system, including delivery and finance reforms, expansion of coverage, and funding to support expanded capacity for patient services. Safety net providers, and FQHCs in particular, have been at the forefront of this change, reforming how and what services they provide to meet the growing needs in their community through the support of ACA funding and increased revenue from newly insured patients. For FQHCs in Detroit, implementing these changes has led to some unanticipated challenges, but has also had a profound effect on their ability to better deliver care to their patients and develop new strategies to meet unmet needs in their community.

Data and Methodology

This report was based on data analysis and qualitative interviews with FQHC leaders. Data submitted by FQHCs to federal government agencies was used to examine year-over-year trends. The Uniform Data System (UDS) reports submitted to the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) include data on patient volume, characteristics and costs. Cost reports sent by FQHCs to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) include information on delivery sites, staffing and productivity.

We also interviewed FQHC leaders in Detroit on a variety of issues, including the state of their health center, how the ACA has affected their business and patients, and what strategies their health center is developing to meet unmet patient needs. Thanks to the following FQHC leaders for meeting with us and sharing their thoughts:

- Joe Ferguson, former CEO – Advantage Health Centers

- Melissa DaSilva, former COO – Advantage Health Centers

- Paul Propson, CEO – Covenant Community Care

- Ricardo Guzman, CEO – Community Health & Social Services Center (CHASS)

Notes

- J.Fangmeier & M. Udow-Phillips. The Uninsured in Michigan, 2014. Cover Michigan 2016 (Ann Arbor, MI: Center for Healthcare Research and Transformation, 2016).

- More broadly, the healthcare safety net includes FQHC look-alike sites, free clinics, and safety net hospitals. However, the focus of this brief is on FQHCs.

- Under the Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA), states have the option to waive the five-year requirement for children and pregnant women for Medicaid or CHIP coverage; however, Michigan does not have this in place.

- The Affordable Care Act established a set of federal grant programs that were set to expire but were continued by subsequent legislation. For example, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), signed into law in April 2015, extended CHIP, the Community Health Center Fund (CHCF) that funds health centers and the National Health Service Corps (NHSC), several maternal and child health programs, and health workforce programs. Funding in these categories was set to expire at the end of FY2015 and was extended through either FY2016 or FY2017. Source: K. Bondalapati,J. Fangmeier, M.Udow-Phillips. Affordable Care Act Funding: An Analysis of Grant Programs under Health Care Reform — FY2010–FY2015. February 2016. Center for Healthcare Research & Transformation. Ann Arbor, MI.

- C.S. Redhead. March 6, 2015. Appropriations and Fund Transfers in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service).

- The community-based prevention grant programs included in this report do not capture all PPHF funding uses. PPHF funds have also been integrated into existing programs that do not mention PPHF.