Introduction

In 2013, the city of Detroit had fewer than 10 working ambulances. A 911 caller with a medical emergency was likely to wait 20 minutes or more for help to arrive, and there was no consistent assessment of data. Emergency medical services (EMS) response and firefighting were completely separate divisions of the fire department, each with single-role providers. Detroit was the only city in the top 200 US population centers without fire apparatus medical responders.1

The EMS infrastructure in Detroit has been greatly strengthened since then; the average time from 911 call receipt to arrival at the patient of a transporting ambulance now approaches eight minutes for priority calls. The city received and deployed more than two dozen donated vehicles, hired and trained additional personnel, implemented the SafetyPAD patient care record, and improved the intake process to more accurately assess call urgency. The city reached an agreement for all Detroit firefighters to be trained as medical first responders. These and other actions reflect ongoing commitment from, and coordination among, the Detroit Fire Department and EMS, the Office of the Mayor, the Detroit Fire Fighters Association, and the Detroit East Medical Control Authority.

Emerging from bankruptcy with greater financial stability, the city has also leveraged resources from the federal government, foundations, and industry sources to modernize EMS operations. At the same time, multi-stakeholder groups in the community continued to come together to advance appropriate use of EMS and emergency department care. Partnerships such as the Detroit Emergency Services Learning Community examined interventions from around the country and saw a good match for Detroit in programs to target frequent EMS users, provide on-site services at EMS “hot spots,” and connect EMS users to needed non-medical social services.

In 2015 and 2016, Altarum Institute worked with public and private stakeholders and EMS experts to support improvements in Detroit EMS. This brief documents our findings and describes future strategies to further strengthen EMS and reduce inappropriate use of emergency resources by addressing underlying population needs.

Investment and improvement in Detroit EMS

The role of EMS has evolved over the last 50 years. Police, firefighters, and emergency medical treatment and transportation are all components of local 911 emergency response capabilities. The way these services are organized and administered within local governments varies around the country. The EMS activity may fall under the management of the Fire Department, or it may be managed as its own independent entity, sometimes in conjunction with private EMS agencies.

In Detroit, and all of Michigan, initial 911 call intake is managed by Law Enforcement, and EMS falls organizationally under the Fire Department (FD). In many cities, fire and EMS operations are completely integrated, with firefighters also serving as medical first responders.

Michigan is unique in its use of Medical Control Authorities (MCAs) to oversee clinical aspects of EMS and create mechanisms for sharing hospital and EMS data within a region. In addition to medical responsibility for public and private EMS transportation services, MCAs are composed by statute from local hospitals who receive EMS patients, and are responsible for protocol development, provision of pharmaceuticals, data submission, and quality assurance. The 62 Michigan MCAs do not receive state funding, and as a result, they are generally set up as non-profit member corporations. Some areas have hospital members supporting the MCAs through dues. The city of Detroit and eastern Wayne County fall under the Detroit East Medical Control Authority (DEMCA). Michigan is the only state that does not require each EMS agency to have a physician medical director. The hospitals in the state of Michigan are also prohibited from charging EMS agencies for medical direction service, which in all other states supports the day-to-day work of medical supervision.

Multiple strategies may be pursued to manage or improve EMS performance, including:

- Process efficiencies guided by operations research or lean process improvement principles such as vehicle location and deployment strategies, 911 call triage, and practices to speed turnaround time at hospital emergency departments;

- Reducing the inappropriate use of EMS for non-urgent care or non-medical needs;

- Addressing significant underlying medical and non-medical needs of EMS “super-users,” who disproportionately require EMS and emergency department care; and

- Outcome based measures using standard data registries such as cardiac arrest (the Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival—CARES) and trauma center databases.

Response time is one metric commonly used to evaluate EMS system performance, although there are many others.2 Response time is defined as the time interval from when the unit is notified of the call until arrival at the scene. This does not include any call processing time, which can be long, or time from arrival on scene to arrival at the patient’s side. The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) has promulgated as a standard for first responders to arrive within 4 minutes 90 percent of the time, and advanced life support to reach 90 percent of indicated EMS calls within eight minutes.3

Among industry experts, there is debate about the application of the eight-minute standard.4 Speed of response has been shown to have no consistent impact on patient outcomes. There may be tradeoffs between speed of response and likelihood of traffic accidents involving EMS vehicles, as well as alternate investments of resources in ways that better improve outcomes. Where time is critical to patient survival, first response must be very fast—within 5 minutes—and often the more important factor is how soon 911 was called. For choking, cardiac arrest, and massive bleeding, only initial bystander response has been shown to affect outcome. A consistently timely response is important to the public’s perception of the quality of local emergency services. Timely response is also an important measure of system efficiency, particularly call handling.

Developments in Detroit EMS: 2010 to 2014

While Detroit has had limited resources for many years, in the early 2010s, Detroit EMS was challenged by collapsing municipal finances and had the fewest resources of any large US municipality.1 EMS response times in Detroit averaged between 18 and 22 minutes, although it was difficult to estimate precisely as the city had no automated call tracking system and no commitment to quality improvement. The Fire Department had six to ten working vehicles to serve a city of nearly 700,000 people. Nationally, vehicle-to-population ratios average two to three vehicles per 10,000 population, which would translate to 140 to 210 vehicles (of all types) in service.

Requirements vary based on geographic area, travel times, and other factors. Detroit does not have the traffic congestion of many other major US cities, but has a very large geographic footprint. Whatever the adjusted standard, fewer than 10 ambulances was clearly not adequate capacity to cover the land mass and population of the city. Private ambulance services were relied upon to supplement Detroit city EMS, although formal agreements were not in place between the city and private EMS providers.

In addition to an EMS infrastructure that badly needed reinforcement, there was evidence that, as in most large US municipalities, a large percentage of 911 calls associated with an EMS response were not for medical emergencies. An assessment of EMS calls in 2010 showed 75 percent of EMS runs were classified as non-urgent or non-transport, and about 50% of EMS patients lacked health insurance at that time.5

In June 2012, as Detroit continued to face financial difficulties, then-Mayor Bing announced the dismissal of 164 firefighters, and over 200 EMS technicians.6 Later that month, Detroit was awarded $22.5 million from the Department of Homeland Security’s Staffing for Adequate Fire and Emergency Response (SAFER) program to retain over 100 jobs, partially mitigating these job losses. This award was the largest grant ever awarded by the Federal Emergency Management Authority.7,8

In March 2013, Mayor Bing announced an $8 million donation from the Downtown Detroit Partnership, allowing 23 new EMS vehicles to be leased to the city to improve public safety. Contributors to the Downtown Detroit Partnership included Roger Penske, Ford Motor Company, Chrysler Group LLC, General Motors Co. (and their UAW partners), Quicken Loans, Inc., the Kresge Foundation, , Platinum Equity LLC, FirstMerit Bank, and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan.9

In July 2013, the City of Detroit filed for bankruptcy. Mayor Bing continued to promote the need for EMS improvements, including increased staffing and equipment.10 All 23 new EMS vehicles were delivered to the city by late 2013. In November 2013, Mayor Mike Duggan was elected into office, inheriting a city under emergency management and multiple long-standing challenges in the delivery of city services.

Investing in the Detroit EMS infrastructure and process: 2014 to present

When Mayor Duggan took office in January 2014, he assembled a lean process improvement team to assess and improve the performance of key city functions. EMS and the fire department were priority areas in this work. EMS reflex time, the interval from 911 call receipt to EMS arrival, along with other metrics of city performance, began to be tracked and reported weekly in a publicly-available, online Detroit dashboard.

The process improvement team instituted a series of projects to improve reflex times on priority calls, including:

- Implementing a digital protocol and training to improve the call intake process and the accuracy of priority coding for service;

- Implementing a computer-aided dispatch system with enhanced GPS tracking; and

- Improving field operations by measuring and working to streamline each segment of the run until the vehicle was back in service.11

Detroit FD EMS began using the SafetyPAD pre-hospital electronic medical record system in 2013. At the beginning of 2014, the average EMS reflex time was 18 minutes for priority runs.12 An average EMS reflex time of 12 minutes was set as an initial target; as times improved, the target was lowered to nine minutes. The ultimate goal is eight minutes.

An important factor in the improvement in EMS performance was a new contract agreement between the Detroit Fire Fighters Association (DFFA) and the City of Detroit. Under the provisions of this new, five-year contract, all fire-fighters were to be trained as medical first responders, allowing more rapid Medical First Responder/Emergency Medical Responder (MFR/EMR) response. Using another SAFER grant awarded from the Department of Homeland Security, cross training of DFD personnel began—Detroit EMTs and paramedics began attending the fire academy, and DFD staff received medical first responder training.

By October 2014, an additional five new ambulances were in operation. By the end of December 2014, the city of Detroit graduated 66 EMTs, and recorded the fastest average reflex time in five years, at 10 minutes and 44 seconds.

As part of the DFFA partnership with the city of Detroit, 31 Detroit firefighters graduated as new medics. These 31 firefighters underwent 12 weeks of training that concluded in January 2015, and were licensed as the city’s newest EMTs. In total, the Fire Department had hired about 100 new staff between December 2014 and May 2015.

As training of Detroit EMS and Fire Department staff continued, the city implemented an Emergency Medical Dispatch System, which helped to streamline prioritization of 911 calls. The system improved accuracy of call classification through correct coding of calls according to national standards. After the first month of implementation, EMS saw significant increases in the number of calls classified as Code 30, or non-life threatening, non-emergent calls. The number of Code 30 calls was 260 in the first week, 350 in the second week, 530 in the third week, and 500 in the fourth week. The city discussed options for diverting greater numbers of non-urgent calls through programs offering alternative forms of transportation and other innovations.

In August 2015, a class of 30 Detroit Public School (DPS) students were the first to train as firefighters and EMTs as a result of a partnership between DPS, the Detroit Fire Department and the Mayor’s office. The new program kicked off at Cody High School’s Medicine and Community Health Academy. The juniors and seniors attended classes three days per week at Cody High School, and also trained at the Detroit Fire Department Academy two days per week.

Detroit FD continued to add vehicles and personnel in 2016. By the first quarter of 2016, EMS added 15 American Emergency Vehicles ambulances, and received replacement ambulances for some of the most worn vehicles in the fleet. EMS had retained a total of 87 field technicians with more than five years of field experience, and hired enough technicians to total 145 field technicians. The city also negotiated memorandums of understanding with four private ambulance services to supplement Detroit FD ambulances during peak times.

Current metrics for Detroit EMS

At the beginning of 2014, the average EMS reflex time—the interval from 911 call receipt to EMS arrival—was 18 minutes for priority runs. By the end of December 2014, the city of Detroit recorded its fastest average reflex time in five years, at 10 minutes and 44 seconds.

In 2015, based on an analysis of EMS run data provided to DEMCA, there were about 100,000 ambulance runs that resulted in transport to a hospital. About three-quarters of these runs were provided by the Detroit Fire Department EMS, while the remaining one-quarter were provided by private ambulance services, primarily Rapid Response, Medstar, Universal, Superior, and DMCare Express.

The majority (83%) of runs in 2015 were transported to one of four locations: Detroit Receiving Hospital (24%) and Sinai Grace Hospital (23%) of the Detroit Medical Center system, Henry Ford Health System Hospital (18%), and St. John Providence Hospital (18%). Detroit Receiving and HFHS are designated as the highest Level I trauma centers, and Sinai Grace and St. John Providence hospitals are designated as Level II centers.

In 2016, DEMCA data show that Detroit FD EMS alone provided about 97,000 transport runs, or about 8,000 runs per month, up from about 6,700 per month at the end of 2015. Detroit FD provided another 18,000 non-transport calls in 2016, for a total response of about 10,000 calls per month.

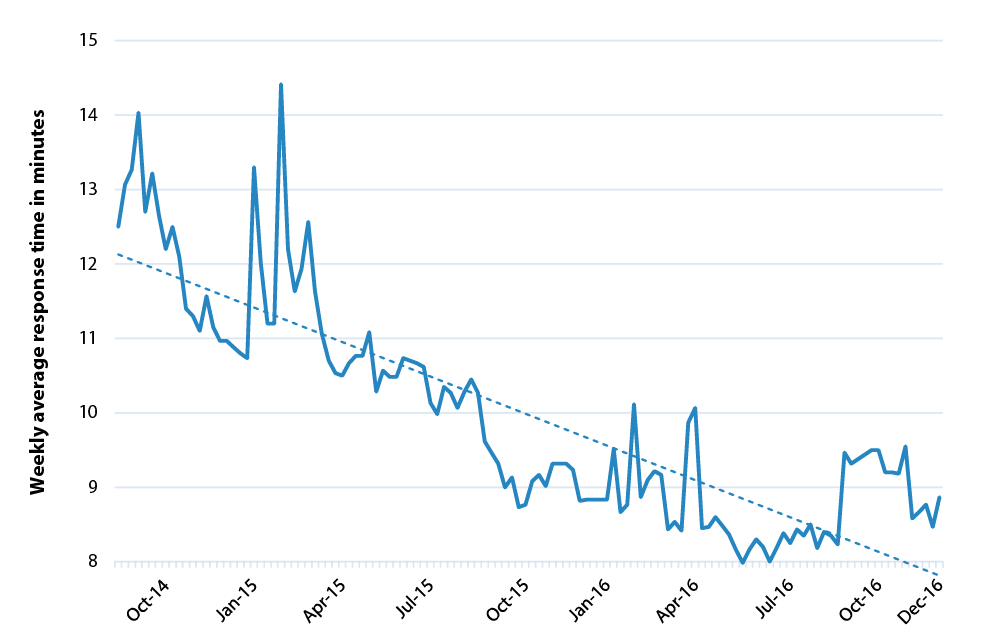

Figure 1 displays the EMS reflex times reported in the weekly Detroit Dashboards from August 2014 through December 2016. The trend is clearly declining and the average response time in 2016 was less than nine minutes for the transporting ambulance, with first responders often arriving at the patient even sooner.

Figure 1: Detroit EMS weekly average priority response times: August 2014–December 2016

Source: Average EMS Priority Response times reported weekly in the Detroit Dashboard. Current and archived dashboards are available at http://www.detroitmi.gov/Detroit-Dashboard. Some spikes in response times such as those in February 2015 correspond to major snow storms. Dotted line is linear trend line.

Community collaborations around emergency medical services in Detroit

Efforts to address underlying health needs and reduce reliance on emergency services in Detroit have been ongoing for many years. For example, under the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Aligning Forces for Quality program, the Greater Detroit Area Health Council worked with primary care providers to reduce unnecessary emergency department use.13 Various initiatives have also been led by the major health systems in Detroit, especially the Detroit Medical Center, Henry Ford Health System, and St. John Providence Health System, around the subset of patients who were frequent users of one or more Detroit emergency departments.

The Voices of Detroit Initiative (VODI), a community-based health care coalition, was created in 1998 to facilitate access to care for underserved populations in Detroit. In early 2012, VODI was tasked by then-Mayor Bing to develop a solution for EMS, including improving coordination of care for high utilizers of emergency services and those who use emergency services for non-urgent issues. VODI began working with community stakeholders to address these needs. Collaboration and some progress was achieved, although challenged by administrative and leadership changes.

By September 2014, VODI, along with key stakeholders, partnered with the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and its contractor, Westat, to continue efforts to reduce non-urgent emergency services through a community-based “learning collaborative.” AHRQ and Westat provided administrative support, access to expertise from around the country, and an inventory of evidence-based innovations to the Detroit Non-Urgent Emergency Services Learning Community (ES LC).

The Detroit ES LC defined three goals around the reduction of non-urgent and frequent use of emergency services: (1) reduce EMS response time; (2) allow EMS to respond to urgent calls efficiently; and (3) connect patients to needed outpatient health, social services, substance abuse and mental health treatment. The Detroit ES LC began convening meetings in October 2014 that included the following key stakeholders: VODI, the Detroit Area Agency on Aging (DAAA), Detroit EMS, the Detroit East Medical Control Authority, the Detroit Fire Department, Detroit Wayne Mental Health Authority, Henry Ford Health System, Ingham County Health Department, the Institute for Population Health, the Neighborhood Service Organization (NSO), and Wayne State University. Representatives from the Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) of Michigan Foundation, BCBS of Michigan Social Mission Department, and Metro Health Foundation

also participated.

The ES LC convened monthly and held additional subcommittee meetings between October 2014 and April 2015, working to develop intervention protocols to accomplish the three goals of the program. By May 2015, the ES LC had established a two-part Better Care Initiative Program Protocol to (1) identify and work with high frequency users of city EMS, and (2) follow up with EMS referrals of non-urgent patients in need of community-based services. A third initiative of interest to the ES LC was to apply the concept of “hot spotting,” or focusing resources on locations in the city with a high concentration of EMS calls. Based on past analysis of Detroit FD EMS call data, the NSO’s Tumaini Center was identified as a primary EMS “hot spot” from which a large number of 911 calls originated. The ES LC worked with the NSO to understand and expand on an existing initiative to provide part-time onsite medical care at the Tumaini Center.

A description and preliminary analysis of each of these three initiatives follows. Data limitations precluded more in-depth analyses. The ES LC closed at the end of 2016 with the expiration of the AHRQ project, but its participating stakeholders are committed to continuing their long-standing coordination around high-need, high-use populations in the city. Much of this prior and continuing participation is pro bono.

Initiative 1: Addressing the needs of frequent users of EMS

Hospitals, health systems, and health departments throughout the nation have long focused on “super-users” or “frequent fliers”—those with significant medical and social needs causing them to disproportionately use emergency medical services and hospital emergency departments.

In Detroit, Henry Ford Health System (HFHS) studied 255 frequent users who visited their emergency department at least 10 times in a year between 2004 and 2013. The researchers found that three-quarters of these frequent users had a substance abuse addiction, a significant portion associated with narcotic use. HFHS found that case management and the creation of individual care plans under their Community Resources for Emergency Department Overuse (CREDO) program significantly reduced emergency department use for these super-users.14

Although frequent users are a very small fraction of EMS transports, these patients typically have complex problems and use multiple hospitals. Detroit EMS retrospectively extracted the names of the top 25 highest utilizers from the SafetyPAD electronic patient reporting system for the period from April 1, 2015 through March 31, 2016. As the program was defined, a care coordinator would establish contact with each super-user and conduct a comprehensive assessment, as well as develop a plan for crisis stabilization. The care coordinator would then set up regular follow-up that would include calls and/or home visits. The intent of the program was to review monthly progress for each of the top 25 super-users and determine additional support services, if necessary. Patients that participated and were successfully connected with appropriate resources would “graduate” the program at the completion of the intervention.

Contact information for the initial set of top 25 users was delivered by Detroit EMS to VODI in April 2016. VODI took preliminary steps to begin contacting these individuals.Of the top 25 super-users identified, 56% (n=14) were unreachable due to outdated or inaccurate contact information. The remaining 44% were unresponsive to the outreach via telephone. The ES LC further discussed the difficulties in reaching this population as an intervention target group, and determined the need to create a data sharing process across organizations to intervene with these patients.

To inform future work with high frequency users, Altarum worked with DEMCA Medical Director Dr. Robert Dunne to examine available EMS call data on these users to describe their characteristics and use patterns. Altarum received the top 25 super-user list in September 2016. Using SafetyPAD to extract Detroit FD EMS data, and the Michigan EMS Information System (MI-EMSIS) for DEMCA to extract private ambulance service data, the team condensed all incident data for the top 25 super-users from January 1, 2014 through November 23, 2016 into a single dataset.

Of the top 25 EMS users, about two-thirds (n=16) were male, and one-third were female. Most commonly, these users were between the ages of 25 and 33 years old (28%, n=7). The 25 super-users called public and private EMS 555 times in 2014, 889 times in 2015 and 702 times in 2016, for a total of 2,146 calls. The 25 users averaged 86 calls per person over the roughly three-year period, or 2.4 EMS calls per month. Studies have shown that, while there is overlap in frequent EMS users from one year to the next, a significant number are high users for a limited time. Looking just at the use patterns for 2015, to more closely align with the time period used to designate these individuals as super-users, EMS use in 2015 averaged 36 times per person, or three times per month.

Nearly 80% of these calls were responded to by Detroit FD EMS, while the remaining calls were fielded by private emergency medical services, most commonly Universal Macomb Ambulance Service. The overwhelming majority (95%) of these calls resulted in treatment by either private or public EMS providers, followed by transport to emergency departments throughout Detroit.

Over 35% (n=563) of super-user calls in 2015 and 2016 recorded the general category “sick person” as the incident type for the purpose of the call. Common primary impressions for calls with the incident type “sick person” included headache, general pain, vomiting, and weakness. The next most frequently identified incident types were: difficulty in breathing/shortness of breath (13%, n=202), chest pain (12%, n=184), no incident type recorded (8%, n=126), and abdominal pain (6%, n=96).

The majority of the top 25 users of EMS suffered from either substance abuse problems, behavioral or psychiatric issues, or a chronic illness—or a combination of these problems. Specifically, seven super-users (28%) had substance abuse problems, two super-users (8%) had a behavioral/psychiatric problem and two super-users (8%) had both a substance abuse and behavioral/psychiatric problem. Nine super-users (36%) had a chronic disease or illness, with five (20%) citing COPD (emphysema/chronic bronchitis), three (12%) citing sickle cell disease, and two (8%) citing hypertension and/or diabetes. One person had both a behavioral/psychiatric problem and a history of sickle cell disease.

Initiative 2: Real-time referrals for non-medical needs

At the October 2014 kick-off meeting of the ES LC, Detroit EMS presented information on a “real-time referral” pilot project between the city and the Detroit Area Agency on Aging (DAAA) that had been in operation for about four months. Detroit EMS personnel in the field were using a 10-question assessment covering nutrition, social, and clinical needs that was implemented as a dropdown menu feature in the SafetyPAD system. Using the results of that assessment, EMS then determined whether to refer the patient to DAAA. DAAA reviewed the referral for eligibility; for those patients that were determined to be 60 years and older, or 18 and older with a disability and a working phone number, DAAA reached out and connected them with the appropriate services and support to address unmet needs.

The ES LC identified the opportunity to support this work with Detroit EMS and DAAA by building onto the existing referral process, and connecting patients younger than 60 years of age to another agency for similar support services. It was determined that those patients younger than age 60 would be referred to the Institute for Population Health (IPH), an organization providing primary care, maternal and child health, behavioral health, and other public health-related programs in the city. Those patients 60 years of age and older would continue to be referred to DAAA. Note that referral to IPH or DAAA did not affect the decision in the field to transport the individual to an emergency department.

Referrals made to both DAAA and IPH were received via fax and email. Patients were contacted within one business day of the referral. Once consent was received from the patient, a care coordinator conducted an assessment and reviewed medical, behavioral, social, and environmental supports of each patient. Based on the outcome of the patient assessment, a care plan was established, and the patient was referred to the appropriate agency based upon his or her individual needs. The expanded ES LC version of the real-time referral intervention launched in May 2015. Through April 2016, Detroit EMS made a total of 288 referrals, 96 to IPH and 192 to DAAA.

Data for 91 referrals made to IPH through October 2015 were made available to Altarum for further analysis. About one-third of the referrals were for individuals between the ages of 55 and 59. Another 22% were between 35 and 44 years old, and 22% between 45 and 54. A slight majority, 55%, were male.

Of the 91 real time referrals made to IPH from Detroit EMS, 23 patients, or about one-quarter of the referrals, consented to participate in the intervention and be connected with a needed service. IPH most commonly connected patients to the Healthy Start program (61%, n=14), a maternal child health program created to reduce perinatal health disparities and address racial disparities in infant mortality. IPH also directly conducted three home visits to referred patients. Additional referrals were made from IPH to external social and clinical services at IPH Dental (n=2), the Heat and Warmth Fund and Water Access Volunteer Effort (n=2), DAAA (n=1), and Well Place Detroit (n=1).

Incorporating the real-time referral form into the electronic SafetyPAD system used by EMS personnel in the field made the process of identifying the patient for referral not unduly burdensome.

As in the super-user intervention, a key to the long-term success of a real-time referral intervention will be identifying individuals or organizations that can take responsibility for follow up in an effective and financially sustainable manner.

Initiative 3: Onsite clinic at a high-need EMS hot spot

The Neighborhood Service Organization (NSO) Tumaini Center is a crisis support center for chronically homeless individuals providing substance abuse treatment, mental health assessment and referral, case management, and other services. Analyses of Detroit FD EMS call data showed that more EMS calls originated at the Tumaini Center than any other address. In addition to being a primary EMS “hot spot,” EMS data and experience indicated that many of the calls from the Tumaini Center were for non-urgent medical needs.

As discussed during the March 2015 ES LC meeting, NSO, in coordination with a local health system, was already implementing internal activities to reduce non-urgent use of emergency services. NSO had a nurse practitioner (NP) onsite on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays between the hours of 8:30 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. The NP provided health care assessments, administered over-the counter-medication, and treated wounds and other minor non-urgent medical needs. The NP was funded by Detroit Receiving Hospital, the most frequent destination for 911 calls originating at the Tumaini Center. In addition to the NP, onsite social workers, case managers, and certified peer specialists were available to individuals at the center Monday through Friday from 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. NSO also partnered with Wayne State University Medical School and Michigan State Medical School to conduct “medicine on the street,” a program sending the NP and outreach teams with medical students out into the community to treat the medical conditions of homeless persons.

Because the onsite clinic began operation more than six years ago, automated call data were not available to quantify any change in 911 calls from the Tumaini Center before and after the opening of the clinic. Altarum was provided with the work schedule for the NP over a two-month period, July and August 2016, including times when the NP was away from the clinic to staff the mobile “medicine on the street” unit. Altarum and Dr. Dunne identified and analyzed Detroit FD and private EMS runs originating from the Tumaini Center during these two months, both during the hours the NP was onsite, and when the NP was not there.

The analysis showed that of the 82 ambulance runs reported to have originated from the Tumaini Center in July and August 2016, 74 of them (90%) occurred when the clinic was closed. 911 calls outside clinic hours were clustered in the evenings from 4PM to midnight. During the 210 hours the clinic was open over these two months, there were only eight ambulance runs originating from the homeless center, one of which was called by the NP for a clinic patient with an urgent medical need.

NSO also provided Altarum with a log of the visits to the NP at the Tumaini Center over this same two-month period—July and August 2016. Included in the log was information on the patient’s complaint and brief descriptions of the diagnosis, intervention, and disposition of the visit. An analysis of these visit data showed that 59 people received 79 visits at the Tumaini Center clinic over the two-month period. Of the 59 people, 46 people visited the clinic once, seven people received two visits, five people received three visits, and one person was seen four times. If July through August 2016 patterns are extrapolated, the onsite NP clinic sees more than 350 individuals annually, or about one-quarter of the 1,400 clients served in 2015 by the Tumaini Center.15

The NP provided an average of 4.2 visits per working day at the clinic. If all EMS calls from the Tumaini Center were converted to clinic visits, it would have doubled the clinic workload to 8.5 visits per working day, or about one visit per hour. These figures suggest that capturing a portion of the remaining EMS call volume would not overwhelm clinic capacity, if it was medically appropriate and able to be diverted to clinic hours. Note that EMS and NSO staff report that visits shown to have originated at the Tumaini Center often involve homeless individuals that have not actually entered the center but are using the address as the pick-up location when calling 911.

About one-third of the onsite clinic visits were provided to male patients, while about two-thirds were provided to females. These proportions are the reverse of the gender distribution of chronically homeless in Detroit, who are about two-thirds male. About three-quarters of the visits were for adults under age 60, while about one-quarter were for those age 60 and older. About 70% of those seen reported having health insurance, usually reporting their coverage as Medicaid or naming one of the Medicaid managed care plans. About 10% of those seen, or about six people, were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, and two others indicated Medicare alone. While insurance information is gathered from patients at the time of the visit, because the costs of the NP are covered by Detroit Receiving Hospital, the Tumaini Center does not seek reimbursement from the patient’s health insurance.

About half of the NP visits at the homeless center were for treatment of a chronic condition, while another 22% of the visits were for conditions that could be either chronic or acute. Chronic conditions included hypertension, psychosis, and hypothyroidism, while conditions that could be chronic or acute included eight cases of dependent edema. About 23% of visits were for conditions that were more likely to be acute, such as a urinary tract infection, or assault. The remaining few visits were for administrative purposes such as a request to have records sent. During the two-month period, EMS was called once for a clinic patient, a pregnant woman having a seizure.

A proposal for health care staffing during evening and weekend hours has been developed to enhance the onsite clinical staff for NSO. The proposal describes the need for experienced health care staff such as physician assistants, emergency medical technicians, nurse practitioners, and other clinicians to be hired for off-hour shifts to reduce the remaining high number of evening and weekend EMS calls and subsequent emergency department utilization.

Of the 82 ambulance runs reported to have originated from the Tumaini Center in July and August 2016, 74 of them (90%) occurred when the onsite clinic was closed.

Directions for the Future

Over the past three years, Detroit has greatly strengthened the city’s EMS infrastructure and processes. Average ambulance response times have been cut in half by leveraging resources provided through donations and government grants, adding vehicles, staff, and technology, assessing and implementing process improvements, and training city firefighters as medical first responders. Like the successful three-year effort to install 65,000 new streetlights around the city, the reduction in EMS reflex times was an early priority of the Duggan administration, and was important not only in restoring a key city function but also in rebuilding trust in city government.

Detroit still has many fewer vehicles in service than the national average—less than 50 even at peak times, where a city the size of Detroit would typically have well over 100. Unit hour utilization rates, a measure of runs per staffed hour in service, remain very high, and more trained staff are needed to put more vehicles in service. Near-term goals for Detroit EMS identified by DEMCA experts include:

- Continuing to refine the integration of the firefighter first responders into the EMS care model;

- Continuing to season the many newly trained EMTs;

- Hiring additional staff; and

- Instituting a comprehensive quality improvement program.

Newly trained staff and firefighter first responders have bolstered needed Basic Life Support (BLS) capabilities in Detroit, but there is a need for more Advanced Life Support (ALS) capabilities—paramedics and advanced EMTs capable of onsite stabilization and treatment of cardiac events, trauma, and other time-sensitive and potentially life-threatening situations. Statewide, Michigan has a shortage of hundreds of ALS providers. However, even with current staff, DEMCA experts find that Detroit could run four more ALS vehicles if the resources were available to convert existing BLS vehicles to ALS, a required investment of about $50 thousand per vehicle.

In addition to continued investment in EMS equipment and staff, existing resources will be more productive if the use of EMS for non-emergency or non-medical needs is reduced. As elsewhere, many of Detroit’s most vulnerable populations struggle with homelessness, mental health and substance abuse issues, lack of transportation, and a historical reliance on emergency care in ways that challenge effective and efficient provision of EMS and other city services.

Progress toward addressing both underlying health and social issues and non-urgent use of EMS would not only impact EMS requirements but would improve the long-term health and wellbeing of the Detroit population.

Reducing overuse of EMS is not the only goal—there is likely to be underuse of services in the city as well. Research suggests that as many as half of stroke victims do not call 911.16 Again, reducing unnecessary EMS use or addressing underlying problems before they require a 911 call will free EMS resources to better handle increased use by those who would benefit from emergency medical care more often or sooner.

Community stakeholders will continue to have an important role in reducing non-urgent EMS use and addressing underlying population health issues. For the stakeholders that came together originally under Mayor Bing and later as the ES LC—including VODI, DAAA, the Detroit Wayne Mental Health Authority, the Neighborhood Service Organization, and Wayne State University—participating with DEMCA may be a mutually beneficial avenue for continuing collaboration. While DEMCA addresses the medical components of EMS care, it could benefit from incorporating the learning community’s focus on social services, public health, behavioral health, and other community services. DEMCA has access to data and has established mechanisms for data sharing that may enable the learning community to more effectively track outcomes and patients who could benefit from additional support. There is precedent for broader MCA participation in communities such as Saginaw Valley and Kalamazoo, who have innovative MCAs that take a collaborative, population-based approach to EMS care.

Improvements in transportation to enable patients to access physician offices or other non-emergency medical care will be another important strategy in reducing inappropriate EMS use. While Medicaid coverage includes some non-emergency transportation, services have historically been inconvenient and unreliable, requiring booking days ahead of time and often running so late that patients miss appointments or are left waiting long periods of time at offices and clinics. A recent innovation in this area is the 2016 teaming of award-winning technology startup SPLT, a carpooling platform, with ridesharing service Lyft to provide non-emergency medical transportation in Detroit and elsewhere.17 SPLT is handling the scheduling and billing while LYFT provides the transportation. Scheduling can be arranged over the phone as well as online and through a mobile application. The partnership is starting with patients of Beaumont Health in southeast Michigan. Area clinics, federally qualified health centers, and hospitals may also be providing transportation services to enable patients to keep their appointments.

Many parts of the country offer alternative transportation after initial EMS assessment. Michigan law and local protocols allow the declaration of a non-emergency after assessment by EMS personnel. In this scenario a patient calling 911 that had a low priority code would get an EMS response. The responder would assess the patient and determine if alternate transport would be suitable and activate a non EMS transport system. This process would allow a large margin of safety for citizens. Detroit investigated this idea in the 1999–2001 paramedic onsite triage (POST) project, but no funding for secondary transportation was ever obtained. Other cities defer transport through a variety of strategies including restricted cab vouchers, non-medical transport vans and telemedicine assessment by physicians from the scene.

Preliminary work by VODI with the top 25 most frequent EMS users highlighted the difficulties that may be encountered in finding and connecting with these individuals outside the EMS and medical system. The Michigan Pathways to Better Health program implemented in Ingham, Muskegon, and Saginaw counties has had some success using dedicated community health workers to connect frequent EMS users to community services.18 The program, based on the Pathways Community HUB model, pairs local EMS with community health worker agencies to identify frequent users, follow up on their underlying needs, and connect them to services, reducing subsequent EMS use.

In Saginaw, the EMS provider saw a reduction of more than 150 transports among the 70 to 80 frequent users identified. Implementation of the program varied by county, but some lessons and results have been documented, and it would be worth connecting with these groups should such a program be considered for Detroit.

Because of underlying medical, social, and financial challenges, many of the people who are high users of EMS are also high users of other city services, including policing and criminal justice, housing support and services to the homeless, and hospital emergency department use. In recognition of the overlap in service to this high-need population, Detroit recently launched participation in the federal Data Driven Justice program. Led by the Detroit Police Department, the program brings together the Detroit Health Department, Police, Fire, EMS, homeless service providers, and the health systems to coordinate on data and strategies for serving this population. The coordination between departments that is the cornerstone of this program offers an opportunity to make substantial progress in identifying and connecting with this high-need population.

Planning for the sustainability of improvements in EMS and in Detroit’s population health must be done with an understanding of the financial implications for city government, private ambulance services, health systems, health plans, and individuals. For Detroit EMS and the ambulance services, the large fixed costs associated with vehicles, infrastructure, and staff on duty mean that small reductions in numbers of calls will not necessarily reduce daily operating costs, although they will reduce health care spending for any trips that would have resulted in an emergency department visit. Today, Detroit EMS resources are still being stretched to maximum use, so there remains plenty of room to reduce non-urgent or non-medical use of EMS and thereby reduce the stresses on existing physical and staff resources.

While there are fixed daily operating costs associated with Detroit EMS services, plenty of room remains to reduce resource stresses associated with non-urgent or non-medical use.

From the perspective of the health systems, the financial incentives around treatment in the emergency department will depend on the extent and nature of health insurance coverage, particularly the Healthy Michigan Medicaid expansion which covers many high need, high use individuals who were previously uninsured. Much depends on the particulars of the payment policies followed by the managed care plans providing Medicaid coverage in Michigan. In an environment where the uninsured rate is historically low, once resources are balanced with the need, both the city and private ambulance services may actually have a financial incentive to transport as many patients as possible using existing infrastructure to maximize reimbursement.

Short-term financial incentives notwithstanding, improving the underlying health and wellbeing of the Detroit population is the ultimate objective of these city and community services. Partnerships are essential for Detroit to find innovative solutions to complex problems. Better population health will benefit not only those directly impacted, but will improve the city’s overall economy and quality of life.

Notes

- Journal of Emergency Medical Services (JEMS) 200-City Survey, an annual survey of local EMS characteristics gathered from the 200 largest cities in the US.

- Myers et al., Evidence-based performance measures for emergency medical services systems: a model for expanded EMS benchmarking. Prehospital Emergency Care 2008;12:141–151

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1710: Standard for the Organization and Deployment of Fire Suppression Operations, Emergency Medical Operations, and Special Operations to the Public by Career Fire Departments.

- Blanchard IE, Doig CJ, Hagel BE, Anton AR, Zygun DA, Kortbeek JB, Powell DG, Williamson TS, Fick GH, Innes GD. Emergency medical services response time and mortality in an urban setting. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2012 Jan-Mar; 16(1):142-51.

- Voices of Detroit Initiative (VODI). Reducing Non-Urgent Emergency Services Learning Community. [Monthly Meeting Minutes]. Retrieved from: https://www.ahrqix.net/LearningComm/LC2/Meetings/Forms/Sorted%20By%20Meeting%20Date.aspx

- Hackney, S. June 2012. Detroit to lay off 164 fire fighters. http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/nation/story/2012-06-25/detroit-firefighter-layoffs/55827788/1

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Fire Prevention and Safety Grants – Grantee Award Year 2014. https://www.fema.gov/fire-prevention-safety-grants-award-year-2014

- Lacy, E. June 2012. Detroit Fire Department Commissioner Don Austin Reacts to Portrayal in ‘Burn’ Film, City Challenges. http://www.mlive.com/entertainment/detroit/index.ssf/2012/10/detroit_fire_commissioner_reac.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+detroit-entertainment+(Detroit+Entertainment)

- Benes, Ross. Detroit welcomes new ambulances, police cars donated by local businesses, Crain’s Detroit Business, August 22, 2013.

- McCallion, T. December 2015. Detroit’s Efforts to Improve EMS Response Includes Dual-Role Fire/EMS. Journal of Emergency Medical Services. September 2016.

- Meetings with Detroit lean process improvement team and Detroit EMS leadership, November 2014 and June 2015.

- Ley, S. May 2016. Detroit EMS Response Times hit Milestone. http://www.clinckondetroit.xom/news/detroit-ems-response-times-hit-milestone

- http://forces4quality.org/detroit-simple-tools-reduce-emergency-department-use.html

- Henry Ford Health System. “Most emergency department ‘super-frequent users’ have substance abuse addiction.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 18 May 2014. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/05/140518092635.htm

- Neighborhood Service Organization 2015 Annual Report states that the Tumaini Center served 1,400 clients in 2015.

- Kamel H. et al. National Trends in Ambulance Use by Patients With Stroke, 1997-2008. JAMA. 2012;307(10):1026-1028. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.285

- Jelinek, J. August 2016. LYFT teams with SPLT to improve Non-Emergency Medical Transport (NEMT). http://techaeris.com/2016/08/08/lyft-teams-splt-improve-non-emergency-medical-transport-nemt/

- https://innovations.ahrq.gov/profiles/community-health-worker-agencies-partner-emergency-medical-service-providers-identify